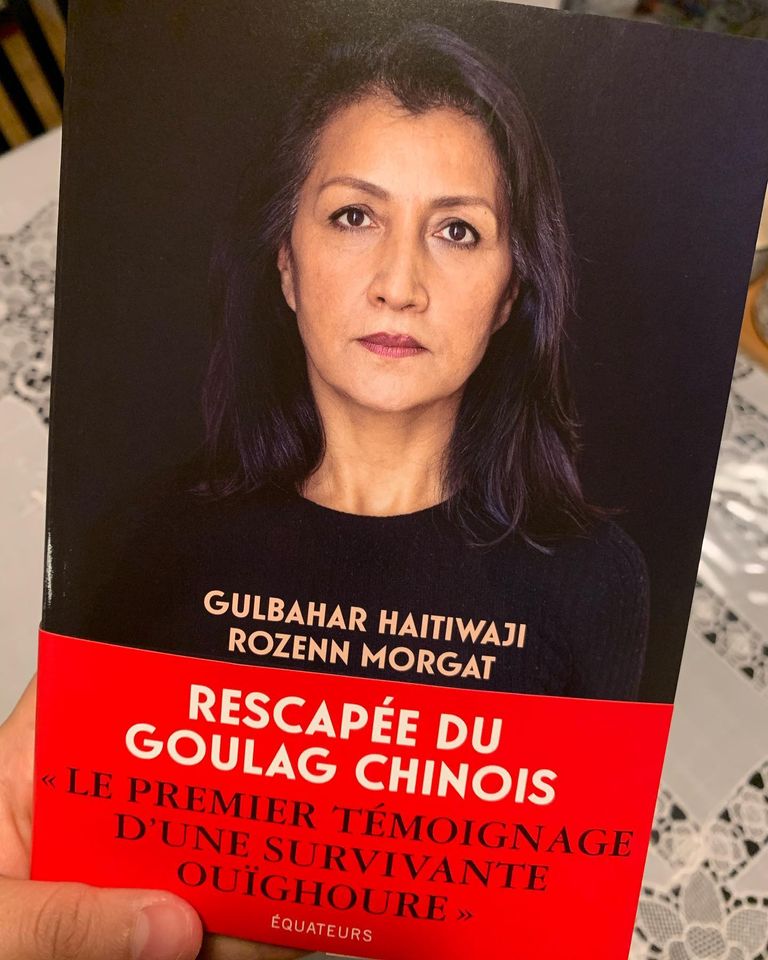

Gulbahar Haitiwaji. Photograph: Emmanuelle Marchadour

After 10 years living in France, I returned to China to sign some papers and I was locked up. For the next two years, I was systematically dehumanised, humiliated and brainwashed

by Gulbahar Haitiwaji with Rozenn Morgat

The Guardian, Jan 12 2021

The man on the phone said he worked for the oil company, “In accounting, actually”. His voice was unfamiliar to me. At first, I couldn’t make sense of what he was calling about. It was November 2016, and I had been on unpaid leave from the company since I left China and moved to France 10 years earlier. There was static on the line; I had a hard time hearing him.

“You must come back to Karamay to sign documents concerning your forthcoming retirement, Madame Haitiwaji,” he said. Karamay was the city in the western Chinese province of Xinjiang where I’d worked for the oil company for more than 20 years.

“In that case, I’d like to grant power of attorney,” I said. “A friend of mine in Karamay takes care of my administrative affairs. Why should I come back for some paperwork? Why go all that way for such a trifle? Why now?”

The man had no answers for me. He simply said he would call me back in two days after looking into the possibility of letting my friend act on my behalf.

My husband, Kerim, had left Xinjiang in 2002 to look for work. He tried first in Kazakhstan, but came back disillusioned after a year. Then in Norway. Then France, where he had applied for asylum. Once he was settled there, our two girls and I would join him.

Kerim had always known he would leave Xinjiang. The idea had taken root even before we were hired by the oil company. We had met as students in Urumqi, the largest city in Xinjiang province, and, as new graduates, had begun looking for work. This was in 1988. In the job ads in the newspapers, there was often a little phrase in small print: No Uighurs. This never left him. While I tried to overlook the evidence of discrimination that followed us everywhere, with Kerim, it became an obsession.

After graduation, we were offered jobs as engineers at the oil company in Karamay. We were lucky. But then there was the red envelope episode. At lunar new year, when the boss handed out the annual bonuses, the red envelopes given to Uighur workers contained less than those given to our colleagues who belonged to China’s dominant ethnic group, the Han. Soon after, all the Uighurs were transferred out of the central office and moved to the outskirts of town. A small group objected, but I didn’t dare. A few months later, when a senior position came up, Kerim applied. He had the right qualifications and the seniority. There was no reason he shouldn’t get the position. But the post went to an employee who belonged to a Han worker who didn’t even have an engineering degree. One night in 2000, Kerim came home and announced that he had quit. “I’ve had enough,” he said.

What my husband was experiencing was all too familiar. Since 1955, when communist China annexed Xinjiang as an “autonomous region”, we Uighurs have been seen as a thorn in the side of the Middle Kingdom. Xinjiang is a strategic corridor and far too valuable for China’s ruling Communist party to risk losing control of it. The party has invested too much in the “new silk road”, the infrastructure project designed to link China to Europe via central Asia, of which our region is an important axis. Xinjiang is essential to President Xi Jinping’s great plan – that is, a peaceful Xinjiang, open for business, cleansed of its separatist tendencies and its ethnic tensions. In short, Xinjiang without Uighurs.

My daughters and I fled to France to join my husband in May 2006, just before Xinjiang entered an unprecedented period of repression. My daughters, 13 and 8 at the time, were given refugee status, as was their father. In seeking asylum, my husband had made a clean break with the past. Obtaining a French passport in effect stripped him of his Chinese nationality. For me, the prospect of turning in my passport held a terrible implication: I would never be able to return to Xinjiang. How could I ever say goodbye to my roots, to the loved ones I’d left behind – my parents, my brothers and sisters, their children? I imagined my mother, getting on in years, dying alone in her village in the northern mountains. Giving up my Chinese nationality meant giving up on her, too. I couldn’t bring myself to do it. So instead, I’d applied for a residence permit that was renewable every 10 years.

After the phone call, my head was buzzing with questions as I looked around the quiet living room of our apartment in Boulogne. Why did that man want me to go back to Karamay? Was it a ploy so the police could interrogate me? Nothing like this had happened to any of the other Uighurs I knew in France.

The man called back two days later. “Granting power of attorney will not be possible, Madame Haitiwaji. You must come to Karamay in person.” I gave in. After all, it was only a matter of a few documents.

“Fine. I’ll be there as soon as I can,” I said.

When I hung up, a shiver ran down my spine. I dreaded going back to Xinjiang. Kerim had been doing his best to reassure me for two days now, but I had a bad feeling about it. At this time of year, Karamay city was in the grip of a brutal winter. Gusts of icy wind howled down the avenues, between the shops, houses and apartment buildings. A few bundled-up figures braved the elements, hugging the walls, but on the whole, there was not a soul to be seen. But what I feared most of all were the ever-stricter measures regulating Xinjiang. Anyone who set foot outside their home could be arrested for no reason at all.

That wasn’t new, but the despotism had become more pronounced since the Urumqi riots in 2009, an explosion of violence between the city’s Uighur and Han populations, which left 197 people dead. The event marked a turning point in the recent history of the region. Later, the Chinese Communist party would blame the entire ethnic group for these horrible acts, justifying its repressive policies by claiming that Uighur households were a hotbed of radical Islam and separatism.

The summer of 2016 saw the entrance of a significant new player in the long struggle between our ethnic group and the Communist party. Chen Quanguo, who had made his reputation imposing draconian surveillance measures in Tibet, was named head of Xinjiang province. With his arrival, the repression of Uighurs escalated dramatically. Thousands were sent to “schools” built almost overnight in the middle of the desert. These were known as “transformation through education” camps. Detainees were sent there to be brainwashed – and worse.

I didn’t want to go back, but all the same, I decided Kerim was right: there was no reason for me to worry. The trip would only take a few weeks. “They’ll definitely pull you in for questioning, but don’t panic. That’s completely normal,” he reassured me.

few days after I landed in China, on the morning of 30 November 2016, I went to the oil company office in Karamay to sign the vaunted documents related to my upcoming retirement. In the office with its flaking walls sat the accountant, a sour-voiced Han, and his secretary, hunched behind a screen.

The next stage took place in Kunlun police station, a 10-minute drive from the company head office. On the way, I prepared my answers to the questions I was likely to be asked. I tried to steel myself. After leaving my belongings at the front desk, I was led to a narrow, soulless room: the interrogation room. I’d never been in one before. A table separated the policemen’s two chairs from my own. The quiet hum of the heater, the poorly cleaned whiteboard, the pallid lighting: these set the scene. We discussed the reasons I left for France, my jobs at a bakery and a cafeteria in the business district of Paris, La Défense.

Then one of the officers shoved a photo under my nose. It made my blood boil. It was a face I knew as well as my own – those full cheeks, that slender nose. It was my daughter Gulhumar. She was posing in front of the Place du Trocadéro in Paris, bundled up in her black coat, the one I’d given her. In the photo, she was smiling, a miniature East Turkestan flag in her hand, a flag the Chinese government had banned. To Uighurs, that flag symbolises the region’s independence movement. The occasion was one of the demonstrations organised by the French branch of the World Uighur Congress, which represents Uighurs in exile and speaks out against Chinese repression in Xinjiang.

Whether you’re politicised or not, such gatherings in France are above all a chance for the community to get together, much like birthdays, Eid and the spring festival of Nowruz. You can go to protest repression in Xinjiang, but also, as Gulhumar did, to see friends and catch up with the community of exiles. At the time, Kerim was a frequent attender. The girls went once or twice. I never did. Politics isn’t my thing. Since leaving Xinjiang, I’d only grown less interested.

Suddenly, the officer slammed his fist on the table.

“You know her, don’t you?”

“Yes. She’s my daughter.”

“Your daughter’s a terrorist!”

“No. I don’t know why she was at that demonstration.”

I kept repeating, “I don’t know, I don’t know what she was doing there, she wasn’t doing anything wrong, I swear! My daughter is not a terrorist! Neither is my husband!”

I can’t remember the rest of the interrogation. All I remember is that photo, their aggressive questions, and my futile replies. I don’t know how long it went on for. I remember that when it was over, I said, irritably: “Can I go now? Are we done here?” Then one of them said: “No, Gulbahar Haitiwaji, we’re not done.”

‘Right! Left! At ease!” There were 40 of us in the room, all women, wearing blue pyjamas. It was a nondescript rectangular classroom. A big metal shutter, perforated with tiny holes that let the light in, hid the outside world from us. Eleven hours a day, the world was reduced to this room. Our slippers squeaked on linoleum. Two Han soldiers relentlessly kept time as we marched up and down the room. This was called “physical education”. In reality, it was tantamount to military training.

Our exhausted bodies moved through the space in unison, back and forth, side to side, corner to corner. When the soldier bellowed “At ease!” in Mandarin, our regiment of prisoners froze. He ordered us to remain still. This could last half an hour, or just as often a whole hour, or even more. When it did, our legs began to prickle all over with pins and needles. Our bodies, still warm and restless, struggled not to sway in the moist heat. We could smell our own foul breath. We were panting like cattle. Sometimes, one or another of us would faint. If she didn’t come round, a guard would yank her to her feet and slap her awake. If she collapsed again, he would drag her out of the room, and we’d never see her again. Ever. At first, this shocked me, but now I was used to it. You can get used to anything, even horror.

It was now June 2017, and I’d been here for three days. After almost five months in the Karamay police cells, between interrogations and random acts of cruelty – at one stage I was chained to my bed for 20 days as punishment, though I never knew what for – I was told I would be going to “school”. I had never heard of these mysterious schools, or the courses they offered. The government has built them to “correct” Uighurs, I was told. The women who shared my cell said it would be like a normal school, with Han teachers. She said that once we had passed, the students would be free to go home.

This “school” was in Baijiantan, a district on the outskirts of Karamay. After leaving the police cells, that was all the information I’d managed to glean, from a sign stuck in a dried ditch where a few empty plastic bags were drifting about. Apparently, the training was to last a fortnight. After that, the classes on theory would begin. I didn’t know how I was going to hold out. How had I not broken down already? Baijiantan was a no man’s land from which three buildings rose, each the size of a small airport. Beyond the barbed-wire fence, there was nothing but desert as far as the eye could see.

On my first day, female guards led me to a dormitory full of beds, mere planks of numbered wood. There was already another woman there: Nadira, Bunk No 8. I was assigned Bunk No 9.

Nadira showed me around the dormitory, which had the heady smell of fresh paint: the bucket for doing your business, which she kicked wrathfully; the window with its metal shutter always closed; the two cameras panning back and forth in high corners of the room. That was it. No mattress. No furniture. No toilet paper. No sheets. No sink. Just two of us in the gloom and the bang of heavy cell doors slamming shut.

This was no school. It was a re-education camp, with military rules, and a clear desire to break us. Silence was enforced, but, physically taxed to the limit, we no longer felt like talking anyway. Over time, our conversations dwindled. Our days were punctuated by the screech of whistles on waking, at mealtime, at bedtime. Guards always had an eye on us; there was no way to escape their watchfulness, no way to whisper, wipe your mouth, or yawn for fear of being accused of praying. It was against the rules to turn down food, for fear of being called an “Islamist terrorist”. The wardens claimed our food was halal.

At night, I collapsed on my bunk in a stupor. I had lost all sense of time. There was no clock. I guessed at the time of day from how cold or hot it felt. The guards terrified me. We hadn’t seen daylight since we arrived – all the windows were blocked by those damned metal shutters. We were surrounded by desert as far as the eye could see. Though one of the policemen had promised I’d be given a phone, I hadn’t been. Who knew I was being held here? Had my sister been notified, or Kerim and Gulhumar? It was a waking nightmare. Beneath the impassive gaze of the security cameras, I couldn’t even open up to my fellow detainees. I was tired, so tired. I couldn’t even think any more.

The camp was a vast labyrinth where guards led us around in groups by dormitory. To go to the showers, the bathroom, the classroom, or the canteen, we were escorted down a series of endless fluorescent-lit hallways. Even a moment’s privacy was impossible. At either end of the hallways, automatic security doors sealed off the maze like airlocks. One thing was for sure: everything here was new. The reek of paint from the spotless walls was a constant reminder. It seemed like the premises of a factory, but I didn’t yet have a handle on just how big it was.

The sheer number of guards and other female prisoners we passed as we were moved around led me to believe this camp was massive. Every day, I saw new faces, zombie-like, with bags under the eyes. By the end of the first day, there had been seven of us in our cell; after three days there were 12. A little quick maths: I’ve counted 16 cell groups, including mine, each with 12 bunks, full up … that made for almost 200 detainees at Baijiantan. Two hundred women torn from their families. Two hundred lives locked up until further notice. And the camp just kept filling up.

You could tell the new arrivals from their distraught faces. They still tried to meet your eyes in the hallway. The ones who’d been there longer looked down at their feet. They shuffled around in close ranks, like robots. They snapped to attention without batting an eye, when a whistle ordered them to. Good God, what had been done to make them that way?

I’d thought the theory classes would bring us a bit of relief from the physical training, but they were even worse. The teacher was always watching us, and slapped us every chance she got. One day, one of my classmates, a woman in her 60s, shut her eyes, surely from exhaustion or fear. The teacher gave her a brutal slap. “Think I don’t see you praying? You’ll be punished!” The guards dragged her violently from the room. An hour later, she came back with something she had written: her self-criticism. The teacher made her read it out loud to us. She obeyed, ashen-faced, then sat down again. All she’d done was shut her eyes.

After a few days, I understood what people meant by “brainwashing”. Every morning, a Uighur instructor would come into our silent classroom. A woman of our own ethnicity, teaching us how to be Chinese. She treated us like wayward citizens that the party had to re-educate. I wondered what she thought of all this. Did she think anything at all? Where was she from? How had she ended up here? Had she herself been re-educated before doing this work?

At her signal, we all stood up as one. “

Lao shi hao!” This greeting to the teacher kicked off 11 hours of daily teaching. We recited a kind of pledge of allegiance to China: “Thank you to our great country. Thank you to our party. Thank you to our dear President Xi Jinping.” In the evening, a similar version ended the lesson: “I wish for my great country to develop and have a bright future. I wish for all ethnicities to form a single great nation. I wish good health to President Xi Jinping. Long live President

Xi Jinping.”

Glued to our chairs, we repeated our lessons like parrots. They taught us the glorious history of China – a sanitised version, cleansed of abuses. On the cover of the manual we were given was inscribed “re-education programme”. It contained nothing but stories of the powerful dynasties and their glorious conquests, and the great achievements of the Communist party. It was even more politicised and biased than the teaching at Chinese universities. In the early days, it made me laugh. Did they really think they were going to break us with a few pages of propaganda?

But as the days went by, fatigue set in like an old enemy. I was exhausted, and my firm resolve to resist was on permanent hold. I tried not to give in, but school went steamrolling on. It rolled right over our aching bodies. So this was brainwashing – whole days spent repeating the same idiotic phrases. As if that weren’t enough, we had to do an hour of extra study after dinner in the evening before going to bed. We would review our endlessly repeated lessons one last time. Every Friday, we had an oral and written test. By turns, beneath the wary eye of the camp leaders, we would recite the communist stew we’d been served up.

In this way, our short-term memory became both our greatest ally and our worst enemy. It enabled us to absorb and regurgitate volumes of history and declarations of loyal citizenship, so we could avoid the public humiliation dished out by the teacher. But at the same time, it weakened our critical abilities. It took away the memories and thoughts that bind us to life. After a while I could no longer picture clearly the faces of Kerim and my daughters. We were worked until we were nothing more than dumb animals. No one told us how long this would go on.

How even to begin the story of what I went through in Xinjiang? How to tell my loved ones that I lived at the mercy of police violence, of Uighurs like me who, because of the status their uniforms gave them, could do as they wished with us, our bodies and souls? Of men and women whose brains had been thoroughly washed – robots stripped of humanity, zealously enforcing orders, petty bureaucrats working under a system in which those who do not denounce others are themselves denounced, and those who do not punish others are themselves punished. Persuaded that we were enemies to be beaten down – traitors and terrorists – they took away our freedom. They locked us up like animals somewhere away from the rest of the world, out of time: in camps.

In the “transformation-through-education” camps, life and death do not mean the same thing as they do elsewhere. A hundred times over I thought, when the footfalls of guards woke us in the night, that our time had come to be executed. When a hand viciously pushed clippers across my skull, and other hands snatched away the tufts of hair that fell on my shoulders, I shut my eyes, blurred with tears, thinking my end was near, that I was being readied for the scaffold, the electric chair, drowning. Death lurked in every corner. When the nurses grabbed my arm to “vaccinate” me, I thought they were poisoning me. In reality, they were sterilising us. That was when I understood the method of the camps, the strategy being implemented: not to kill us in cold blood, but to make us slowly disappear. So slowly that no one would notice.

We were ordered to deny who we were. To spit on our own traditions, our beliefs. To criticise our language. To insult our own people. Women like me, who emerged from the camps, are no longer who we once were. We are shadows; our souls are dead. I was made to believe that my loved ones, my husband and my daughter, were terrorists. I was so far away, so alone, so exhausted and alienated, that I almost ended up believing it. My husband, Kerim, my daughters Gulhumar and Gulnigar – I denounced your “crimes”. I begged forgiveness from the Communist party for atrocities that neither you nor I committed. I regret everything I said that dishonoured you. Today I am alive, and I want to proclaim the truth. I don’t know if you will accept me, I don’t know if you’ll forgive me.

How can I begin to tell you what happened here?

Iwas held in the camp at Baijiantan for two years. During that time, everyone around me – the police officers who came to interrogate prisoners, plus the guards, teachers and tutors – tried to make me believe the massive lie without which China could not have justified its re-education project: that Uighurs are terrorists, and thus that I, Gulbahar, as a Uighur who had been living in exile in France for 10 years, was a terrorist. Wave after wave of propaganda crashed down upon me, and as the months went by, I began to lose part of my sanity. Bits of my soul shattered and broke off. I will never recover them.

During violent interrogations by the police, I kowtowed under the blows – so much so that I even made false confessions. They managed to convince me that the sooner I owned up to my crimes, the sooner I’d be able to leave. Exhausted, I finally gave in. I had no other choice. No one can fight against themselves for ever. No matter how tirelessly you battle brainwashing, it does its insidious work. All desire and passion desert you. What options do you have left? A slow, painful descent into death, or submission. If you play at submission, if you feign losing your psychological power struggle against the police, then at least, despite it all, you hang on to the shard of lucidity that reminds you who you are.

I didn’t believe a word of what I was saying to them. I simply did my best to be a good actor.

On 2 August 2019, after a short trial, before an audience of just a few people, a judge from Karamay pronounced me innocent. I barely heard his words. I listened to the sentence as if it were nothing to do with me. I was thinking about all the times I had asserted my innocence, all those nights I had tossed and turned on my bunk, enraged that no one would believe me. And I was thinking about all those other times when I had admitted the things they accused me of, all the fake confessions I had made, all those lies.

They had sentenced me to seven years of re-education. They had tortured my body and brought my mind to the edge of madness. And now, after reviewing my case, a judge had decided that no, in actual fact, I was innocent. I was free to go.

• Some names have been changed. Translated by Edward Gauvin. This is an edited extract from Rescapée du Goulag Chinois (Survivor of the Chinese Gulag) by Gulbahar Haitiwaji, co-authored with Rozenn Morgat and published by Editions des Equateurs