Summary:

The White Paper published by the State Council Information Office in July 2021 stated that “rural labor transfers in the Uyghur Region averaged over 2.82 million yearly from 2017 until 2020, with 61.44% in the south.”[1] In his more recent address in January 2023, by Erkin Tuniyaz, the Chairman of the Uyghur Region, reported there were 3.03 million transfers of rural laborers in 2022.[2] This indicates state-imposed labor transfers are continuing at a larger scale.[3] In its work report for 2021, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) administration proudly noted that rural surplus labor placement reached 14.33 million between 2016 and 2021.[4] Some people may have been transferred more than once.[5] The Chinese government mobilized all state apparatus, existing or prepared facilities, private and state-owned companies, and the local cadres to systematically transfer such a vast number of workers inside and outside the Uyghur Region.

Part one of this report briefly outlines key takeaways on Uyghur forced labor, summarizing existing research on the matter.

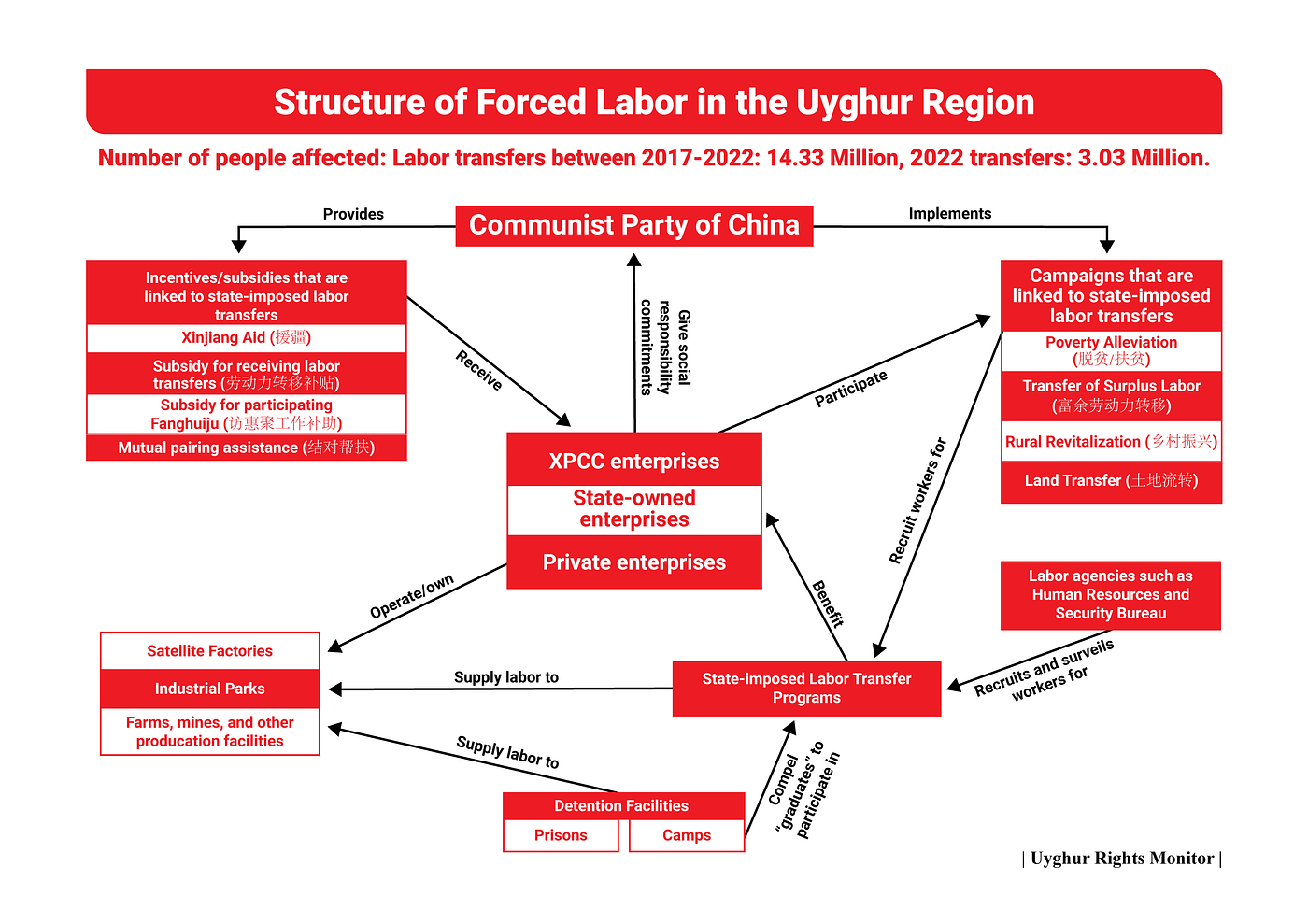

Part two explores the structure of forced labor in the Uyghur region and state agencies behind the state-imposed labor transfer programs targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic people.

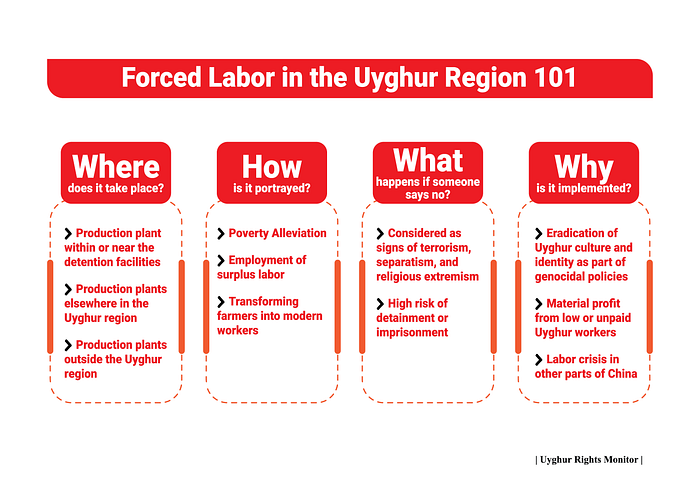

Part 1. Forced Labor in the Uyghur Region 101

According to a report on labor transfer programs in the Uyghur Region, conducted by Nankai University Poverty Alleviation Research Group, state-imposed labor transfers in the Uyghur Region “not only reduces the Uyghur population density in Xinjiang but is also an important method to influence, integrate, and assimilate Uyghur minorities,”.[6] Along with other programs such as “poverty alleviation,” “Xinjiang aid,” and “pairing up and becoming the family,” the Chinese government carries out social engineering and surveillance of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other local Turkic people in the region. This is not only to make material profit from the forced labor of Uyghurs but also to eradicate Uyghur identity as part of its genocidal policies in the Uyghur Region. These forced labor schemes run parallel to the full-scale operation of regionwide “re-education camps” and the state-planned expansion of various industries, including solar, raw materials, and textile, to name a few, in the Uyghur Region, aligning with the objectives in the “Made in China 2025” strategy.[7]

The Chinese government unveiled the “Outline of the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region” in May 2016, a few months before the onset of mass detentions. The plan emphasized the role of the village working group in “visiting people’s feelings and gathering people’s hearts” on the one hand. It also called for deepening the reform of state-owned enterprises and enhancing the vitality, control, and influence of the state-owned economy on the other.[8] It describes the labor transfer programs as part of the “poverty alleviation” efforts of the regional government, where Uyghurs are the primary target. The plan details also show how the government granted state-owned and private enterprises play a pivotal role in the labor transfer program. The four prefectures in southern Xinjiang, for instance, actively implement poverty alleviation models, such as “satellite factories,” “poverty alleviation workshops,” and “township factories,”[9] attracting numerous state-owned and private enterprises to move their production plants to the Uyghur Region under the name of “Xinjiang Aid” to exploit land, labor, and resources in the Uyghur Region. The intention behind these programs is parallel to the “population optimization” in the Uyghur Region which is meant to dilute Uyghur populations and forcibly integrate them into Han society.[10]

When the methods of state-imposed labor transfer programs are carefully examined, it becomes clear that the Xinjian Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), the People’s Government, and both private and state-owned companies have worked closely together to implement a regionally comprehensive system of policies under the directive of the Communist Party. In terms of camp-centered forced labor, the Communist Party of China (CPC) Xinjiang oversaw top organizations including the Xinjiang Political and Legal Affairs Commission and gave local-level party secretaries instructions on how to coordinate between various departments, which were primarily responsible for the decision-making processes behind the “re-education” camps as was mentioned in a previous URM report on “re-education camps.”[11]

However, the camps are not the only source of state-imposed labor transfers in the Uyghur Region. Uyghurs and other local people outside of the camps are another source for state-imposed labor transfer programs. By frequently visiting families, calling people for interrogation, and closely monitoring their everyday activities, grassroots organizations primarily observe, investigate, and collect information about residents.[12] Through initiatives like “pairing programs,” state-owned or private businesses played a vital part in the surveillance of Uyghur families. The White Paper published by the State Council Information Office in July 2021 stated that “Rural labor transfers averaged over 2.82 million yearly from 2017 until 2020, with 61.44% in the south.”[13] In more recent address of the Erkin Tuniyaz, the Chairman of the Uyghur region, in January 2023, he says there were 3.03 million transfers of rural laborers in 2022, an indication of continuation of state-imposed labor transfers at a larger scale.[14] In its work report for 2021, the XUAR administration proudly noted that rural surplus labor placement reached 14.33 million times between 2016–2021 (some people may be transferred more than once).[15] To transfer such a vast number of workers inside and outside the Uyghur Region, the Chinese government mobilized all state apparatus, existing or prepared facilities, private and state-owned companies, and the local cadres to build a network that resulted in systematically forced labor schemes.

Existing reports and research on Uyghur forced labor outline the following pattern: enterprises operating in the Uyghur Region, state-owned or private, are at very high risk of exposure to Uyghur forced labor. This is not only because they make material profit from low or unpaid workers, but also because of their “social responsibility commitments” to the state to show their loyalty to the Communist Party.[16] In a report from August 2022, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery concluded that there is reasonable evidence to support the occurrence of forced labor in the Region, where the situation involves the exploitation of indigenous people, denying them their freedom to choose and subjecting them to harsh working conditions.[17] In the United States, an increasing number of companies are now sanctioned because of their complicity with the Uyghur genocide, and forced-labor-tainted goods are being prevented from entering the U.S. market within the scope of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).

Where Does Forced Labor Take Place?

People held in prisons or labor camps are often required to work for state-owned and private enterprises.[18] However, this only constitutes a small portion of state-imposed forced labor in the Uyghur Region. State-imposed labor transfers occur within prefectures, cross-prefectures, and beyond Xinjiang in mainland China. Forced labor transfers within the prefecture are likely to be in production plants or industrial parks near individual’s home. The domestic supply of laborers to these factories is highly likely from detention facilities, such as “re-education camps” or prisons. The “surplus labor” has two destinations: production plants and industrial parks located in other prefectures in the Uyghur Region or other provinces in China. Overall, forced labor can be:

1) Within or near the detention facilities (camps and prisons)

Uyghurs who are detained in camps or prisons work in factories, farms, and mines built inside or near the detention facilities. At least 135 re-education camps that are close to or coexist with factories have been identified by reporters.[19]

2) Within the Uyghur Region

Uyghurs are transferred to production plants or industrial parks in the Uyghur Region, in their own hometown or other cities in the region. Uyghurs living in rural areas are transferred to other cities systematically to work in a wide range of industries.[20] A White Paper from 2020 revealed that the regional government transferred 221,000 individuals from their hometowns to other parts of the Uyghur Region as rural surplus labor between 2018 and June 2020.[21]

3) Receiving production plants in other provinces of China

Uyghurs are also transferred to production plants outside the Uyghur Region, located in various industrialized cities across the mainland. Official records show that 4,710 Uyghurs were “relocated” to Shandong province between 2017 and 2018.[22] Between 2017 and 2019, a total of 80,000 Uyghur laborers were transferred to factories across the mainland.[23]

What Happens If Someone Refuses to Participate in State-imposed Labor Transfer Programs?

Uyghur have no right to say refuse state-imposed labor transfers. In such cases, they are persuaded or coerced to participate in the labor transfer programs.[24] “If the government tells you to go, you have to go.”[25] Anyone who rejects or objects to labor transfers any kind of rejection or objection may be perceived defying state law, failing to adapt to state policies, having extremist ideology and would face serious consequences as below:

1) Considered as a sign of terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism.

Forced labor programs are rooted in the idea of using labor as an anti-terrorism strategy. Uyghur individuals who oppose state-imposed initiatives that claim to promote vocational skills and poverty reduction are viewed as aligning themselves with the “three evils,” which are terrorism, extremism, and separatism. These “three evils” serve as the justification for the CCP’s crackdown and criminalization in the Uyghur region, including the camp system.[26]

2) Risk of detainment or imprisonment

In the Uyghur Region, labor transfer initiatives involve forcibly relocating Uyghur workers to factories in the region or China proper.[27] Individuals coerced into working in specific industries or locations against their will.[28] Testimonies from Uyghur workers reveal a persistent fear that those who resist or attempt to leave their assigned jobs face the ominous prospect of internment or imprisonment, underscoring the pervasive threat that accompanies these programs. [29]

What are the conditions that transferred laborers encounter?[30]

Forced labor facilities expose workers to extremely alarming circumstances that violate their fundamental human rights. These facilities hosting transferred Uyghur workers typically restrict their freedom of movement and prevent them from returning home whenever they want. Workers are unable to leave their jobs and risk punishment if they voice any problems. The residential areas are segregated and constantly monitored with cutting-edge technology. Strict regulations are enforced by specialized security personnel, simulating a military setting. The workers frequently have open-ended contracts that are negotiated between businesses and state agencies rather than directly with the workers themselves. This causes issues like unauthorized wage deductions and earnings that are far below the minimum wage set by the government. In addition, workers are forced to work without proper protection equipment.[31]

Part 2. The Structure of Forced Labor in the Uyghur Region

The Supply: Making Uyghurs Available for Exploitation

Transferring Uyghurs to factories in China proper is not new. Since the 2000s, the Chinese government has actively encouraged the movement of Uyghur workers in the name of promoting ‘inter-ethnic fusion’ (民族交融) and ‘poverty alleviation’ (扶贫).[32] However, with the onset of the mass detention campaign, along with other genocidal policies in the Uyghur Region, the nature and scope of state-imposed labor transfers have become more repressive.[33] The government orders local working groups to knock door-to-door to identify people who could be considered “surplus labor”[34] and instructs them to transfer at least one person in every family.[35] The regional government then implements various strategies to transfer “surplus labor” to various locations in and outside of the Uyghur Region collaborating with grassroots organizations, companies, and state agencies. Strategies include establishing “satellite factories” and “poverty alleviation workshops” for “rural surplus labor.”[36] CCP official documents on the subject proudly mentioned that they assured that “zero-employment households found jobs within 24 hours once they were identified.”[37]

According to the Xinjiang Development and Reform Commission[38], Uyghurs from so-called “re-education centers” (internment camps) had grown significantly due to economic activity for the Uyghur Region by late 2018.[39] Shohrat Zakir, Chairman of the XUAR, said in October 2018 that there would be a “seamless link between learning in school and employment in society” for “trainees” who finished their periods in the internment camps to be hired by “established firms.”[40] Indeed, the Kashgar regional administration alone intended 100,000 people to go through “vocational training” in 2018 while giving strong incentives to the businesses that hired them.[41] Under the pairing initiatives such as the “school + enterprise + industry” framework, in which individuals from re-education and vocational training programs belonging to Uyghurs and other local people are dispatched to different cities in the Uyghur Region.[42] One online ad for “government-imposed Uyghur labor” offers factories 1,000 workers aged 16–18, emphasizing Xinjiang workers’ strengths like semi-military management and resilience and adding that managers of receiving factories can request 24/7 Xinjiang police presence.[43]

A White Paper issued by China’s State Council Information Office in 2020 claims that the XUAR government initiated a three-year initiative from 2017 to 2019 to enhance its poverty alleviation plan across 22 counties in southern parts of the Uyghur Region, which is dominated by Uyghurs, along with four regimental farms within the XPCC. Mostly government agencies and companies are directly involved in the state-imposed labor transfer program under the campaigns such as “one-on-one help” (对一帮扶), “counterpart support” (对口支援), “mutual pairing help” (结对帮扶), “rural revitalization” (乡村振兴), “one company help one village” (一企一村帮扶), “thousands of enterprises help thousands of villages” (千企帮千村), etc.[44]

Furthermore, CPC agencies create “surplus labor” by adopting a unique program called “land transfer” (土地流转). Once Uyghurs and Kazakhs leave their land, they are classified as “surplus labor” (富余劳动力) and poor households are subjected to labor transfer” programs.[46] Until 2019, Shaya County of Aksu alone had undertaken efforts to investigate and advance land transfer, tackling persistent challenges that have impeded both land transfer and expanded operations by using the so-called “Cooperative + Farmers” model, “Company + Cooperative + Farmers” model and “Family Farm + Farmers” model. In total, these initiatives involve 500,000 acres of land and affect 21,793 households with 77,971 individuals.[47] Through land transfer, the government not only “handles” the land problem of Chinese companies moving into the Uyghur Region but also creates a large number of “surplus laborers” by blocking the main income source of Uyghur farmers and leaving them with no option but to work in manufacturing companies. Chronicles of the Poverty Alleviation Task Force of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Political Consultative Conference “Fanghuiju” Village Working Team describe the farmers who “handed over their land” to work in the newly established satellite factories in their hometown as “farmers liberated from their land and transformed industrial workers.”[48] Under the directives of CPC Xinjiang, representatives from the enterprises (both state-owned and private), participate in grassroots working groups, such as Fanghuiju, and become an integral part of the forced labor practices in the Uyghur Region, from surveillance of households to determine people who must participate in labor transfer programs.[49] The social responsibility commitments of enterprises made to the CPC require companies to participate in these working groups with select Communist Party members working in their companies.[50]

The Demand: How Companies Are Incentivized to Use Uyghur Forced Labor

The National Development and Reform Commission (改革委) designed the Counterpart Assistance to Xinjiang (or Xinjiang Aid) program, which assigns industrialized provinces of the mainland to cities and towns in the Uyghur Region to assist in economic development.[51] It is also a pathway for private and state-owned enterprises in the mainland to move into the Uyghur Region by building massive industrial parks in the rural areas and employing transferred Uyghur workers in their production plants. For example, the widely circulated photo of detainees in the Lop County Number 4 Re-education Center is in Beijing Industrial Park, established by Xinjiang Aid from Beijing Huairou District Government.[52] Despite the forced labor conditions in the Beijing Industrial Park revealed to the international community, it has now upgraded to an autonomous level industrial park for its “successes” over the last decade.[53] According to an article published in Tianshan Net in September 2022, private and state-owned enterprises from the industrialized provinces are strongly incentivized to move into the Uyghur Region, establishing industrial parks and satellite factories, transferring lands of the local people, and employing transferred “surplus labor” to their production facilities inside and/or outside of the Uyghur Region.[54]

As for companies operating in the Uyghur region, various government entities facilitate the employment of state-imposed labor transfers. These entities include, but are not limited to, the Xinjiang State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Committee,[55] the Xinjiang Department of Industry and Information Technology,[56] the Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.[57] The main body that coordinates between enterprises and local state agencies in assigning state-imposed labor transfers is the Xinjiang Poverty Alleviation and Development Office, which also works with the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce[58] to bring private enterprises to the southern part of the Uyghur region in preparation for job transfers.[59] The Xinjiang Department of Human Resource and Social Management has a system called the “rural laborer job transfer management system,” which monitors every worker in real time, with assigned personnel to update information about the worker.[60]

The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC)[61] plays a crucial role in overseeing the financial and operational aspects of (SOEs) in China, including those located in regions like Xinjiang. The SASAC is the primary agency responsible for managing and overseeing the operations of central government-owned enterprises. It is directly under the State Council, which is China’s cabinet and is led by a chairman appointed by the State Council. The SASAC is responsible for approving major investments and financing decisions for SOEs, as well as appointing and removing their top executives. Considering labor transfers and their relevance, asset management departments hold a significant position in the overall landscape. Their oversight of SOEs’ financial well-being and regulatory adherence could potentially impact decisions related to labor transfer and forced labor practices. Given their involvement in evaluating various aspects of SOE operations, including financial health, equity management, and asset transactions, these departments might contribute to the orchestration and coordination of labor transfer programs, either directly or indirectly. The level of scrutiny and control exercised by these departments over SOEs’ activities underscores their potential influence on labor-related initiatives and policies, especially within the framework of state-owned enterprises operating in Xinjiang. State-owned enterprises from other provinces of China also actively participated in the labor transfer programs, either by building up their “satellite” factories in the Uyghur Region or transferring them to their production plants in the mainland.

For instance, the XPCC SASAC manages and oversees the SOEs of XPCC. The director, appointed by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region government, leads the XPCC SASAC and reports to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region SASAC. The China New Construction Group Cooperation (or China Xinjian), which is the name XPCC uses in its economic activities, has more than 2900 subsidiaries operating within and outside the Uyghur Region.[62] Current Chairman Li Yifei is the Deputy Secretary of the CPC Xinjiang standing committee, a member of the 20th Central Committee, and a Political Commissar of XPCC. The findings of several reports and research articles detail how XPCC-owned state enterprises are complicit with the forced labor practices across the Uyghur Region. The XPCC was sanctioned by the United States Department of Treasury on July 30, 2020, under Global Magnitsky Sanctions. However, its parent agency, neither the Xinjiang State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission nor the China National State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, are sanctioned by the United States or any other countries concerned with the Uyghur forced labor. Many companies that are owned by Xinjiang SASAC are complicit with Uyghur forced labor, participating in family visits, and receiving transferred laborers.

For example, Xinjiang Zhongtai Group, owned by the Xinjiang SASAC, sent a group of representatives, led by the Deputy Secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Zhongtai Group, to stay in Siyek Village, Keriye County of Hoten, to participate in the “visiting family” program, along with the local CPC cadres.[63] The company has received transferred laborers from Southern Xinjiang several times, with military-style uniforms, to work in its factories.[64] For their commitment to the Communist Party and employment of transferred workers, several subsidiaries of Xinjiang Zhongtai, most of which are in the textile sector, received more than 25 million RMB subsidy from various government bodies, such as the Finance Bureau, Development and Reform Committee of the XPCC, Economic and Technological Development Zone Social Development Bureau, only in the first half of 2020, under notices such as “Notice on Effectively Doing a Good Job in Guaranteeing Employment Policies for the Organized Transfer of Surplus Labor in Urban and Rural Area.”[65]

Conclusion

Uyghur forced labor, one of the most severe human rights violations in the modern world,[66] is imposed by the clear directive of the Communist Party of China, mobilizing all its apparatuses in the Uyghur Region and beyond, not only to gain the material benefit from the low or unpaid Uyghur workers but also to monitor them in the forced labor facilities. The forced labor network in the Uyghur region separates workers from their land and families to serve the purpose of eradicating Uyghur identity and culture in the Uyghur Region. Numerous state agencies, from top to bottom, are mobilized to transfer workers to production facilities, with participation and support from enterprises both at the supply and demand side of the “forced labor market” in the Uyghur Region. Hence, companies operating in or sourcing from the Uyghur Region or sourcing from a company that has participated in Xinjiang Aid put their supply chain at high risk of exposure to systematic forced labor schemes across and beyond the Uyghur Region.

[1] “(新疆各民族平等权利的保障)(全文)”[Guarantee of Equal Rights of All Ethnic Groups in Xinjiang” (full text)], State Council Information Office, July 14th, 2021, Online; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang,” Xinhuanet, September 17, 2020, Online; “China’s White Paper on Forced Labour Suggests Unease at Western Pressure”, The Guardian, September 18th, 2020, Online; Laura T. Murphy & Nyrola Elima, “In Broad Daylight”, Sheffield Hallam University, May 2021, Online.

[2] Erkin Tuniyaz, “政府工作报告”, [2021 Xinjiang Government Work Report], Xinjiang Daily, January 23rd, 2023, Online.

[3] Erkin Tuniyaz, “政府工作报告”, [2021 Xinjiang Government Work Report], Xinjiang Daily, January 23rd, 2023, Online.

[4] Shohret Zakir, “2021年新疆政府工作报告” [2021 Xinjiang government work report], Research Office of the People’s Government of Hubei Province, March 8, 2021, Online.

[5] Shohret Zakir, “2021年新疆政府工作报告” [2021 Xinjiang government work report], Research Office of the People’s Government of Hubei Province, March 8, 2021, Online.

[6] “新疆和田地区维族劳动力转移就业扶贫工作报告” [Nankai University Poverty Alleviation Research Group, Poverty Alleviation Work Report on Uyghur Labor Transfer and Employment in Hotan, Xinjiang ], April 6th, 2019. Online

[7] “新疆维吾尔自治区国民经济和社会发展: 第十三个五年规划纲要” [National economic and social development of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region: Outline of the thirteenth five-year plan], May 2016. Online

[8] “新疆维吾尔自治区国民经济和社会发展 第十三个五年规划纲要” [Outline of the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region], May 2016, Online. As a comprehensive economic and social plan, this initiative initially undertaken by the government coincided with the onset of the CCP’s current genocidal policy against Uyghurs and other local populations. In the plan, it directed that the Uyghur populated four prefectures, and border areas in the southern part of the Uyghur Region should be the main battlefields for poverty alleviation. It also required all level cadres to sign responsibility letters for poverty alleviation and underlined the actual performance of poverty alleviation and development work as an important basis for selecting and employing cadres.

[9] “新疆南疆四地州就业扶贫问题及对策建议” [Pan Hao, Problems and Countermeasures of Employment Poverty Alleviation in the Four Prefectures of Southern Xinjiang], Tribune of Social Sciences in Xinjiang, No 2, 2019, Online.

[10] Amy Lehr, “Addressing Forced Labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”, CSIS, July 2020, Online; “Risks and Considerations for Businesses and Individuals with Exposure to Entities Engaged in Forced Labor and other Human Rights Abuses linked to Xinjiang, China”, U.S. Department of State, July 13th, 2021, Online; “Uyghur forced labour in Xinjiang and UK value chains”, U.K. Parliament, March 17th, 2021, Online; “Study of Supply Chain Risks related to Xinjiang forced labour”, Government of Canada, April 6th, 2022, Online.

[11] “Authorized to “Wash Clean the Brains” — Agencies at Play Amid Mass Detention of Millions in the Uyghur Region,” Uyghur Rights Monitor, August 2, 2023, Medium, Online.

[12] “地区人民检察院开展‘坚定理想信念, 对党绝对忠诚, 做新时代忠诚干净担当的人民检察官’, 发声亮剑活动” [Regional People’s Procuratorate launches “speak up and brandish the sword” activities, emphasizing ‘firm ideals and beliefs, absolute loyalty to the party to create a new generation of loyal and incorruptible People’s procurators], Altay News, February 12, 2019, online; “全疆检查干部亮剑:始终对党绝对忠诚, 全面履行检查职责”, [All cadres in Xinjiang’s People’s Procuratorate participate in “speak up and brandish the sword” activities: Absolutely loyal to the party to the end, and comprehensively perform procuratorial responsibilities], Tianshan News via Sohu News, June 1, 2017, online; “阿图什市人民法院开 展发声亮剑活动,人人发声,个个亮剑,再次掀起发声亮剑新高潮” [Atush City People’s Court launches “speak up and brandish the sword” activities, everyone is speaking up and brandishing their swords, the activities have reached new heights], Kizilsu Television via WeChat, January 10, 2019, online; “石河子市人民法院举行发声亮剑大会” [Shihezi City People’s Court holds “speak up and brandish the sword” mass meeting], Kizilsu Television via WeChat, April 17, 2018, online.

[13] “(新疆各民族平等权利的保障)(全文)”[Guarantee of Equal Rights of All Ethnic Groups in Xinjiang” (full text)], State Council Information Office, July 14th, 2021, Online; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “Employment and labor rights in Xinjiang,” Xinhuanet, September 17, 2020, Online; “China’s white paper on forced labour suggests unease at Western pressure”, The Guardian, September 18th, 2020, Online; Laura T. Murphy & Nyrola Elima, “In Broad Daylight”, Sheffield Hallm University, May 2021, Online.

[14] Erkin Tuniyaz, “政府工作报告”, [2021 Xinjiang government work report], Xinjiang Daily, January 23rd, 2023, Online.

[15] Shohret Zakir, “2021年新疆政府工作报告” [2021 Xinjiang government work report], Research Office of the People’s Government of Hubei Province, March 8, 2021, Online.

[16] Shilei Wu, Hongjie Zhang & Taoyuan Wei, “Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure, Media Reports, and Enterprise Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies”, MDPI, July 29th, 2021, Online; “关于新疆如意纺织服装有限公司等四家公司破产案意向投资人招募公告”, Xinjiang Bankruptcy Enterprise Disposal Information Network, July 14th, 2023, Online.

[17] Ruth Ingram, “Forced Labor in Xinjiang, UN Rapporteur Confirms: “It’s Enslavement, a Crime Against Humanity.”, Bitter Winter, August 29th, 2022, Online.

[18] “Against Their Will: The Situation in Xinjiang”, Bureau of International Labor Affairs, 2021, Online; Alexander Kriebitz & Raphael Max, “The Xinjiang Case and Its Implications from a Business Ethics Perspective”, Human Rights Review, May 22nd, 2020, Online; Nicole Morgret, “Shifting Gears”, C4ADS, June 30th, 2022, Online.

[19] Allison Killing and Megha Rajagopalan, “The factories in the camps,” Buzzfeed, December 28, 2020, Online.

[20] “今天,2887名劳动力被转移,这里的纺企老板再无需担心用工荒!未来三年还将转移10万人”[ Today, 2,887 laborers have been transferred, and the owners of textile enterprises here no longer need to worry about labor shortages! Another 100,000 people will be transferred in the next three years], Fangyou Net, June 27th, 2017, Online.

[21] State Council Information Office, Full Text: Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang, Xinhua, September 2020, Online

[22] “国家援疆新闻平台专访山东省援疆总指挥、新疆喀什地委副书记杨国强” [Interview with Yang Guoqiang, Chief Commander of Shandong Province and Deputy Secretary of Xinjiang Kashgar Party Committee], China Development Network (中国发展网), April 27th, 2018, Online.

[23] Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, Danielle Cave, Dr. James Leibold, Kelsey Munro & Nathan Ruser, “Uyghurs for sale”, ASPI, March 1st, 2020, Online; “European Parliament resolution of 17 December 2020 on forced labour and the situation of the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region”, European Parliament, December 17th, 2020, Online.

[24] John Sudworth, “‘If the others go I’ll go’: Inside China’s scheme to transfer Uighurs into work,” BBC News, March 2th, 2021, Online

[25] Eva Dou and Chao Deng, “Western Companies Get Tangled in China’s Muslim Clampdown,” The Wall Street Journal, May 16, 2019, Online.

[26] Murphy, L. and Elimä, N. “In Broad Daylight: Uyghur Forced Labour and Global Solar Supply Chains.” Sheffield Hallam University Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice, 2021. Online; “新疆局地组织民众识别75种宗教极端活动” [Locally organize people in Xinjiang to identify 75 kinds of religious extremist activities], Observer Network (观察者网), December 24th, 2014, Online.

[27] Ibid; “新疆脱贫军令状:2018年要坚决打好精准脱贫攻坚战” [Xinjiang Poverty Alleviation Military Order: In 2018, we must resolutely fight the battle against poverty], Xin Wen (辛闻), China Net: China Poverty Alleviation Online (中国网·中国扶贫在线), February 7th, 2018, Online; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “Employment and labor rights,”; Adrian Zenz, “Coercive labor, forced human displacement, and links to mass atrocities in Xinjiang’s two forced labor programs,” presented at The Xinjiang Crisis: Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, Justice Conference, Newcastle University, September 1st, 2021, Online; “2021年新疆经济增长7.0%” [Xinjiang’s economy to grow by 7.0% in 2021], Xinjiang Daily (新疆日报), February 7th, 2022, Online.

[28] “对口援疆·做到群众心坎上” [Xinjiang Aid, to the hearts of the masses], Anhui Guoyuan Financial Holdings Group Co. Ltd (安徽国元金融控股集团有限责任公司), July 26th, 2018, Online; “和田外出务工人员在江西南昌高新企业就业掠影” [Hoten migrant workers find employment in Jiangxi Nanchang’s high-tech enterprises], Hotan People’s government (和田市人民政府), April 8th, 2019, Online.

[29] “新疆自治区人力资源和社会保障厅:强化区内劳务协作促进长期稳定就业” [Xinjiang Human Resources and Social Security Department: Strengthening labor cooperation in the region to promote long-term stable employment], Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国人力资源和社会保障部), January 11th, 2019, Online; Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, ‘Inside China’s push to turn Muslim minorities into an army of workers’, New York Times, December 30th, 2019, Online.

[30] The conditions in the camp are adopted from the SHU report, Laundering Cotton and based on extensive review of Chinese, Uyghur, and Kazakh language sources about stories of Uyghur and other minoritized workers in forced labor facilities. Laura T. Murphy, “Laundering Cotton”, Sheffield Hallam University, November 2021, Online; OHCHR Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, August 31st, 2022. “广东企业招用新疆籍劳动者指引(试用)” [Guidelines for Guangdong Enterprises to Recruit Xinjiang Workers (Trial)], Human Resource and Social Security Department of Guangdong Province, January 18th, 2019, Online; “《一》重要通知