A WeChat post by the state television station in Linxia shows how a mosque was closed and turned into a cloth shoe poverty alleviation workshop in Huangniwan Village in August 2018, Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province, China, May 14, 2020. © 2020 China Linxia News Network

Curbing Islam via ‘Consolidation’ Policy in Ningxia, Gansu Provinces

HRW, November 22, 2023

(New York) – The Chinese government is significantly reducing the number of mosques in Ningxia and Gansu provinces under its “mosque consolidation” policy, in violation of the right to freedom of religion, Human Rights Watch said today.

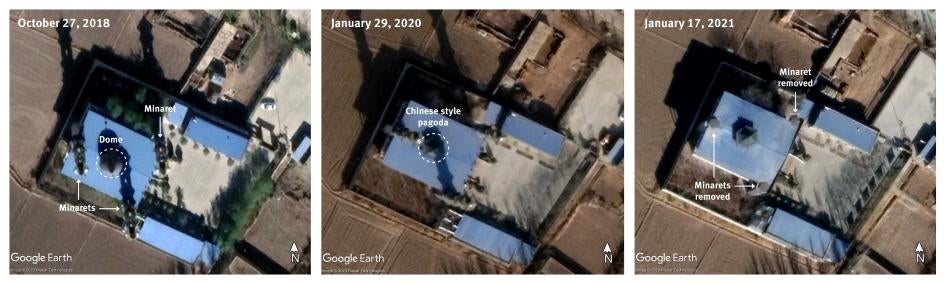

Chinese authorities have decommissioned, closed down, demolished, and converted mosques for secular use as part of the government’s efforts to restrict the practice of Islam. The authorities have removed Islamic architectural features, such as domes and minarets, from many other mosques.

“The Chinese government is not ‘consolidating’ mosques as it claims, but closing many down in violation of religious freedom,” said Maya Wang, acting China director at Human Rights Watch. “The Chinese government’s closure, destruction, and repurposing of mosques is part of a systematic effort to curb the practice of Islam in China.”

Chinese law allows people to practice only in officially approved places of worship of officially approved religions, and authorities retain strict control over houses of worship. Since 2016, when President Xi Jinping called for the “Sinicization” of religions, which aims to ensure that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the arbiter of people’s spiritual life, state control over religion has strengthened.

“Mosque consolidation”[1] is referenced in an April 2018 central CCP document that outlines a multi-pronged national strategy to “Sinicize” Islam, or make it more Chinese.[2] It instructs the CCP and state agencies throughout the country to “strengthen the standardized management of the construction, renovation and expansion of Islamic religious venues.” The document notes that a central principle behind such “management” is that “there should not be newly built Islamic venues,” in order to “compress the overall number [of mosques].” While there can be exceptions, the document states that “there should be more [mosque] demolitions than constructions.”

Ma Ju, a US-based Hui Muslim activist who has been in contact with Hui in China affected by the policy, told Human Rights Watch that it is part of efforts to “transform” (转化) devout Muslims in order to redirect their loyalty toward the CCP: “Government officials first approach those Communist Party members who are also Hui Muslims … then they move onto ‘persuading’ students and governmental workers, who are threatened with school probation and unemployment if they continue with their faith.”

Available government documents suggest that the Chinese government has been “consolidating” mosques in Ningxia and Gansu provinces, which have the highest Muslim populations in China after Xinjiang.[3] Since 2017, Chinese authorities in Xinjiang have damaged or destroyed two-thirds of the region’s mosques, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). About half have been demolished outright.

In Ningxia, Human Rights Watch has verified and analyzed videos and pictures posted online by Hui Muslims and used satellite imagery to corroborate them in order to examine the policy’s implementation in two villages. Of these villages’ seven mosques, four had significant destruction: three main buildings had been razed and the ablution hall of one was damaged inside. The authorities have removed the domes and minarets of all seven mosques.

Human Rights Watch is unable to determine the number of mosques shuttered or repurposed throughout Ningxia and Gansu, as official documents do not give precise details. In a forthcoming research report, two scholars on Hui Muslims, Hannah Theaker and David Stroup, have estimated that one-third of mosques in Ningxia have been closed since 2020.[4] A March 2021 Radio Free Asia report estimated that between 400 and 500 mosques faced closure in Ningxia, which had 4,203 mosques as of 2014.

The Chinese government claims that the mosque consolidation policy aims to “reduce the economic burden” on Muslims, especially those who live in impoverished and rural areas.[5] Actions against mosques often take place as the Chinese government relocates villagers from these areas, consolidating several villages into one.[6] The government also claims that as different Islamic denominations share the same venues, they learn to become more “unified” and “harmonious.”

Some Hui Muslims have publicly opposed the policy, despite government censorship. In January 2021, Ningxia officials indicted five Hui for “creating disturbances” after they led 20 people to oppose the policy at the village Party chief’s office. People have also protested mosque closures and demolitions, as well as the removal of domes and minarets in Ningxia, Gansu and other Hui Muslim regions, such as Qinghai and Yunnan.[7]

Ma Ju told Human Rights Watch that mosque consolidation aims to dissuade people from going to pray at mosques: “After removing the minarets and domes, local governments would start removing things that are essential to religious activities such as ablution halls and preacher’s podiums.”

Ma Ju said the government has sought to discourage religious practice: “When people stop going, they [the authorities] would then use that as an excuse to close the mosques.” He said that the authorities install surveillance systems in the remaining “Sinicized” mosques: “After the mosques are converted, the local governments strictly monitor attendance at the remaining mosques,” he said. “In the beginning, they would check the attendees’ national identification cards. Then they install surveillance cameras … to flag [those prohibited from mosques, including] Communist Party members or children.”

Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “[e]veryone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” One has the right to manifest their “religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.” The Chinese government should reverse its Sinicization campaign on religions, review and repeal laws and regulations that restrict the right to freedom of religion, and release those detained for peaceful criticism or protest against such restrictive policies.

Foreign governments, particularly member countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), should press the Chinese government to cease their mosque consolidation policy and the broader Sinicization campaign.

“The Chinese government’s policies of Sinicization show a blanket disregard for freedom of religion not only of all Muslims in China, but all religious communities in the country,” Wang said. “Governments concerned about religious freedom should raise these issues directly with the Chinese government and at the United Nations and other international forums.”

For additional detail about mosque closures and satellite images of the changes, please see below.

Mosque Closures

Large-scale mosque closures last took place in China in the 1950s, after the Chinese Communist Party took over the country in 1949. Authorities razed or consolidated an estimated 90 percent of Ningxia’s mosques prior the Cultural Revolution in 1966. After the end of the Cultural Revolution a decade later, people in China rebuilt their religious lives, constructing many mosques even as the Chinese government maintained strict control over religion. Today, authorities retain control over personnel appointments, publications, finances, and seminary applications for the five officially approved religions.

Since 2016, when President Xi Jinping called for the “Sinicization” of religions, state control over religion has tightened. Going beyond controlling religion by dictating what constitutes “normal,” and therefore legal religious activity, the authorities now seek to comprehensively reshape religions to make them consistent with CCP ideology and to promote allegiance to the party and President Xi.

Under Xi, Chinese officials have undertaken a broad effort to curb the influence of Islam, which the authorities often conflate with terrorism and backwardness. Reducing the number of mosques is a key element of this policy. Numerous policies are placing growing restrictions on the lives of Hui Muslims, who have assimilated with Han, the majority ethnic group in China.

The Chinese government has revised or added new laws to tighten religious control, including the Measures on the Administration of Religious Activity Venues, which came into force in July 2023. The measures require religious venues to indoctrinate followers in CCP ideology, and prohibit them from “creating conflicts … between sects,” or from receiving funding unless it is approved by the state.

A central part of “Sinicization” of religions is to excise perceived “foreign” influences from religions. Followers of Islam, who also suffer growing Islamophobia among the Chinese public, and Christianity have borne the brunt of these xenophobic policies. In 2015, authorities removed crosses from churches and in some cases demolished entire churches in Zhejiang Province, considered the heartland of Chinese Christianity. The campaign was publicly described as an effort to remove “illegal structures” that do not comply with zoning requirements, but according to an internal provincial directive, it was designed to reduce the prominence of Christianity in the region.

In Xinjiang, the Chinese government’s aggressive assimilationist policies in ethnic minority regions have led to severe abuses that amount to crimes against humanity, such as cultural persecution. These abuses include the systematic destruction of numerous mosques.

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

In 2018, the Ningxia Communist Party Committee promulgated an "implementation document”[8] to carry out the national strategy to “Sinicize” Islam. The policy of “consolidating mosques” is also referenced in a March 2018 government document from Yinchuan City[9], the capital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. The document states that the government aims to “strictly control the number and scale of religious venues,” and that mosques should adopt “Chinese architecture styles.” It says that the Yinchuan City government should promote the “integration and combination of mosques” to “solve the problem of too many religious venues.”

Human Rights Watch has found many documents published by local governments in Ningxia that mention the term “mosque consolidation,” but only a few provide details:[10]

- In Zhongwei City, authorities stated in 2019 that they had “completed the alteration of 214 mosques, consolidated 58 mosques, and banned 37 unregistered religious venues.” Zhongwei City had 852 mosques in 2009, according to an official mosque directory of Ningxia.

- The Qingtongxia City government wrote in 2020 that it had “combined six mosques,” and “the scale and frequency of large-scale and cross-regional religious activities dropped by 30.6 percent and 62.5 percent year-on-year respectively.” Qingtongxia had 69 mosques in 2009.

- A January 28, 2021, indictment issued by the Zhongning County Procuratorate said that the authorities decided to shut down three out of the five mosques in the area. It stated that the authorities decided which mosques to close by determining the “distances between mosques, their construction, and the size of their main halls.” Local authorities reported that they closed the three mosques because they had no main halls.

- In the town of Jingui, the authorities stated in 2021 that they “thoroughly rectified more than 130 locations with Islamic architectural features … and pursued ‘mosque integration’ in an orderly manner.”

- In an annual update, authorities in Baitugang Township, Lingwu City, said they “consolidated five mosques” in 2021.

Human Rights Watch further examined the impact of the mosque consolidation policy in two Ningxia villages where we obtained additional information.

Case 1: Liaoqiao Village, Wuzhong City

Liaoqiao Village is an administrative entity that incorporates nine settlements about 12 kilometers southeast of Wuzhong City. About 55 percent of the population are Hui Muslims. In 2013, the village had six mosques.[11] Satellite imagery showed that prior to 2020, all of them had Islamic architectural features, including minarets and round domes. These features were removed from three of the mosques between January and August 2020. The most important buildings—the main halls—of the other three were destroyed. It is unlikely that they will continue to function as mosques.

Case 2: Liujiagou Mosque, Chuankou Village, Xiji County

Liujiagou Mosque is situated in Chuankou Village, in the mountainous region of Xiji County in southern Ningxia, where about 60 percent of the population is Hui. The mosque was first built in 1988 and then rebuilt in 2016 with a larger main hall featuring two minarets and a dome. According to satellite imagery, these minarets and the dome were removed sometime between 2019 and 2021.

In a series of videos that Human Rights Watch obtained in January 2023 and then verified and geolocated, the interior of the ablution hall, which is essential for daily prayers, is being demolished. An anonymous source knowledgeable about the demolition said that Liujiagou Mosque had been closed since at least early 2022. The source also said that of the 96 mosques in the town of Xinglong, about 60 had been closed and that “the town authorities want to demolish the ablution halls of those mosques that have been closed.”

In this tweet video that is verified and geolocated by Human Rights Watch, the interior of the ablution hall, which is essential for daily prayers, is being demolished.

Gansu Province

The Gansu provincial government issued a document implementing the April 2018 central Chinese Communist Party document to “Sinicize” Islam.[12] There is also evidence to suggest that the mosque consolidation policy is being implemented in Gansu Province.

- In Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture in 2020, the Hezheng County government “reduced and combined 10 mosques, and completed the alteration of the Islamic architectural features of … 31 of them.”

- Also in Linxia in 2020, the Yongjing County government started “five mosque consolidations, and completed one” in Xiaoling Township.[13]

- In Dazhai Township in 2020, Kongtong District, Pingliang City, the government “altered 26 mosques [and] consolidated 2 mosques.”

- In Guanghe County, known as “Little Mecca” with the majority of its population being Hui Muslims, authorities in 2020 “cancelled the registration of 12 mosques, closed down 5 mosques, and improved and consolidated another 5.”[14]

Case 3: Huangniwan Village, Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province

In a WeChat public post by Linxia Television Station, the local government said in 2019 that it had closed one mosque out of three in a village with 2,440 people. The village originally had one mosque in the 1990s, but “disagreements” led some villagers to build two other mosques. In 2019, after “painstaking ideological education and guidance work,” a phrase that usually implies some combination of persuasion and coercion, the local authorities decommissioned one of the mosques and turned it into a “workspace” and “cultural center” as part of their “poverty alleviation” efforts.

[1] This policy is sometimes referred to as “合坊并寺,” “合坊建寺” or “合村并寺” in Chinese.

[2] The document, known as “Document No.10,” has not been made public by the Chinese government. It was leaked as part of the “Xinjiang Papers.” See pages 5 and 6, which enumerate the policy to reduce the number of mosques in China.

[3] China had 39,135 mosques as of 2014, according to official figures. The top three regions with the largest number of mosques are Xinjiang (24,100), Gansu (4,606) and Ningxia (4,203). See “版权所有 中国伊斯兰教协会, “2015最新中国清真寺数量及分布,” March 3, 2015. http://www.chinaislam.net.cn/cms/news/media/201503/03-8001.html.

[4] Hannah Theaker and David Stroup, Making Islam Chinese: Religious Policy and Mosque Sinicization in the Xi Era, forthcoming.

[5] On rural relocations, see: Emily Feng, “In Rural China, Villagers Say They're Forced From Farm Homes To High-Rises,” NPR, August 10, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/08/10/893113807/china-speeds-up-drive-to-pave-rural-villages-put-up-high-rises.

[6] Laochi consolidated villages outside Yinchuan City (西夏区兴泾镇十里铺村涝池组合坊) used to have at least three mosques (Laochi South Mosque, Laochi North Mosque, and Laochi East Mosque), according to a 2009 Ningxia mosque directory. As authorities consolidated the villages, only two mosques were rebuilt. See: 北京市建壮咨询有限公司宁夏分公司, “十里铺村涝池组合坊并寺异地重建项目1#寺施工变更公告[变更公告],” July 1, 2021, http://www.nxggzyjy.org/ningxiaweb/002/002001/002001002/20210701/caf25360-441c-4c22-af20-f84545427878.html and 十里铺村涝池组合坊并寺异地重建项目2#寺施工招标文件, “十里铺村涝池组合坊并寺异地重建项目2#寺施工招标公告,” January 18, 2021, http://www.nxggzyjy.org/ningxiaweb/002/002001/002001001/20210118/a2408fc2-8b66-40bb-9add-a80a9bbb7a39.html.

[7] The forthcoming research by academics Theaker and Stroup also showed how the mosque consolidation policy is being implemented in Qinghai Province, albeit under different policy names, and that it will likely be implemented in Yunnan Province, given how the authorities’ Sinicization efforts have started in Ningxia before the same methods are used elsewhere.

[8] The document, “Implementation Opinion on the Strengthening and Improving of Islamic Work under the New Situation (关于加强和改进新形势下伊斯兰教工作的实施意见),” was promulgated by the Ningxia provincial Party Committee in 2018 and is mentioned in this report by Ningxia University. See 宁夏大学新闻中心, “牢固树立马克思主义民族观宗教观 扎实推进各项工作实践,” September 27, 2018, https://news.nxu.edu.cn/info/1022/8037.htm.

[9] 中共银川市委、银川市人民政府关于印发乡村振兴战略银川三年行动计划的通知(银党发〔2018〕9号 2018年3月8日)(Chinese Communist Party Yichuan City Committee, Yichuan People’s Government notice on printing ‘Three Year Action Plan for Yichuan City’s Strategy on Invigorating the Countryside’, March 8th 2018). Copy on file with HRW.

[10] See, for example, “Zhongwei City Government 2023 Annual Work Report (2023年政府工作报告),” December 23, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231024151840/http://www.nxzw.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/zfgzbg/202212/t20221223_3896583.html; Litong District Representatives Examine Various Reports “(利通区各代表团审议各项报告),” which mentions the problem of handling those who lost their jobs as a result of the mosque consolidation policy, January 8, 2021, https://archive.ph/oHVhp; “Lu Jun Examines Guyuan City Ethnicity and Religious Work (陆军调研固原市民族宗教工作),” November 29, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20231023210136/https://www.nxtzb.gov.cn/contents/MZZJ/2021/11/8013.html, where a top Ningxia official in-charge of ethnic and religious affairs examined the progress of mosque consolidation policy as part of Xi’s Sinicization of Islam.

[11] A 2009 directory of Ningxia mosques listed five mosques in the area; one additional mosque was constructed in 2013.

[12] The date of promulgation of the Gansu implementation measures (中共甘肃省委办公厅、甘肃省人民政府办公厅《关于加强和改进新形势下伊斯兰教工作的实施意见》) is unclear, though the earliest official meeting that referenced it took place in July 2018. See: http://tstz.tianshui.com.cn/news/MZZJ/2018/731/187311010583IGJ84EKDH6EF0HB6E9E.html

[13] P.224, Yongjing 2020 annual yearbook.

[14] P.89, Guanghe 2020 annual yearbook.