For these Sunday posts in January, I want to listen to how people with immigration or refugee experiences find sustenance and purpose in difficult times.

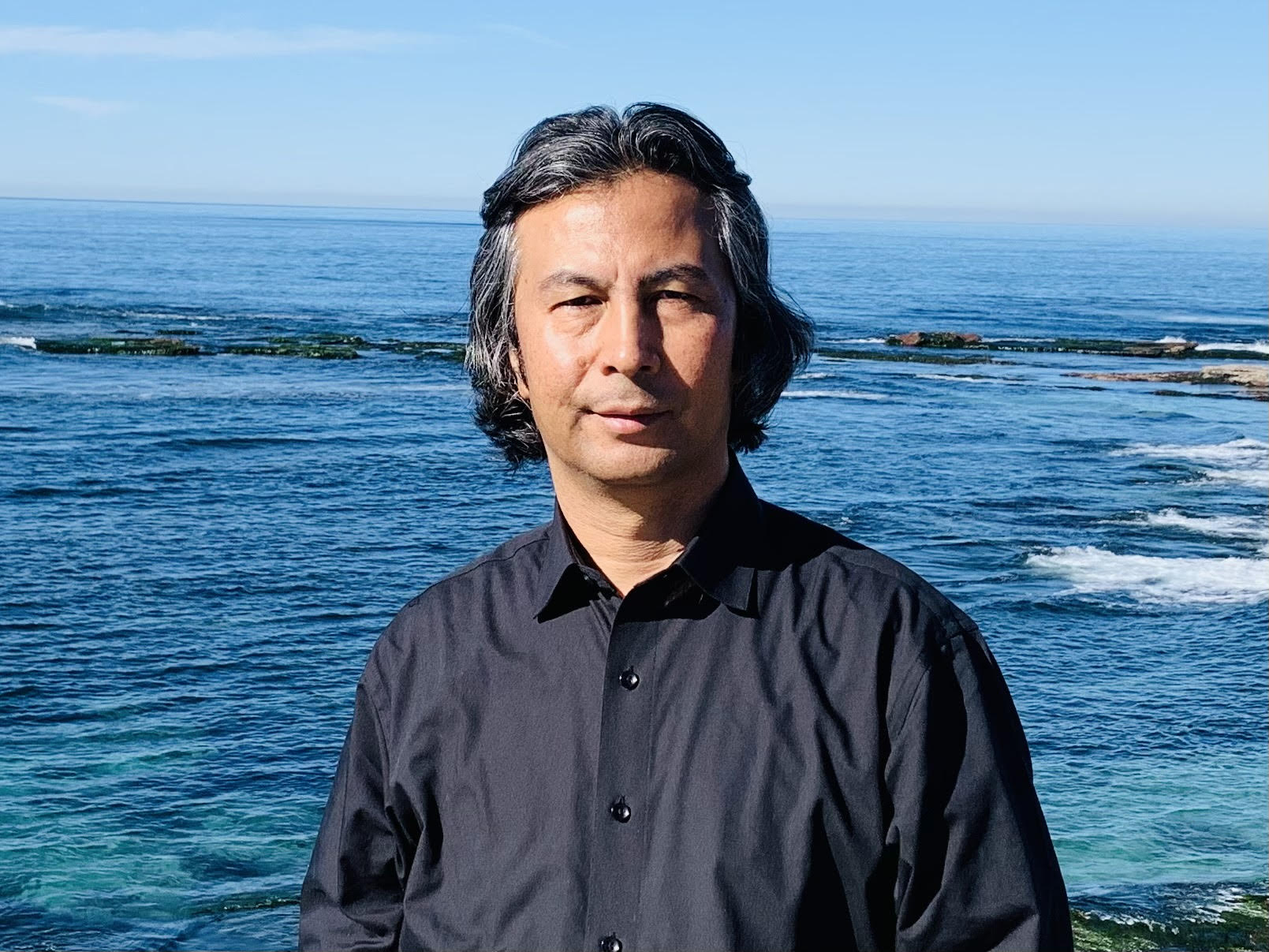

A few years ago, I wrote a story about an anthropologist doing impressive work chronicling the daily lives of the Uyghur people, an ethnic minority facing atrocious persecution, surveillance, and cultural violence from the Chinese government. In the course of my research, I began corresponding with Tahir Hamut, a prominent Uyghur poet and intellectual.

Tahir told me about fleeing his home as his friends, one by one, were disappeared into “reeducation” internment camps. He told me about settling in suburban Washington, D.C., driving for Uber and helping his wife and their daughters adjust to a new life. And he sent a copy of his application for political asylum, a heartrending account of the choices that confronted his family – to leave the vibrant artistic culture of their home city of Urumchi, to leave without even telling his parents and asking their blessing, lest they face punishment for his escape.

It was a stunning narrative, and I wished it was more widely available. Now it is, in Tahir’s new memoir Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide. The book is a vivid, human-scaled account of one family’s attempt to do their best amid terrible circumstances. For a situation that can feel hopeless and as distant as, well, western China, that’s a valuable thing.

I wrote a few years ago about why, at least for me, the Uyghur story is so difficult to grasp:

To begin with, most Americans need an introduction to Xinjiang, a desert and mountainous province twice the size of Texas, and to Uyghur (pronounced wee-gur) people, a Muslim ethnic minority of more than 11 million who have long lived under Chinese rule, with varying degrees of stability.

Throughout the twentieth century China has feared Uyghur separatism and has responded violently to conflicts between Uyghurs and the 10 million Han (Chinese ethnic majority) people who the government sent to settle in the region. In 2014, China declared a “People’s War on Terror,” building thousands of police checkpoints and launching a green-card system that restricted movement for millions of Uyghurs, especially young men. It sent police into Uyghur homes with a checklist to assess individuals’ “risk” of violence based on criteria such as whether they pray daily or have studied Arabic. In a culture where religion is central to identity, it banned fasting during Ramadan, required Uyghur shops to sell alcohol, and restricted practices as personal as women’s veils and men’s beards.

The scale of the injustice is precisely why Tahir’s book is so helpful. He understands that a compelling story doesn’t need overly dramatic writing. He gives a ground’s-eye view of a smothering surveillance system that included checkpoints with advanced phone-scanning technology and incentives for neighbors to report each other. He writes of sleeping in warm clothing because others had been arrested at night and taken to camps without the chance to dress. When a friend acknowledges doing the same, they laugh together, the only way they know to cope with the increasing terror.

He watches as once-lively neighborhoods grow quiet: “The naan bakeries at every crossroads were being boarded up; the fruit sellers’ carts were disappearing from the streets; the crowds whose bustle brought the neighborhood to life were dwindling.”

Some of the most powerful details are the some of the most mundane: The low-level party officials who take Tahir to dinner and force him to pick up the tab, or the Muslim clerics who dance on TV to an inane Chinese pop song because it might prevent harassment from a party official.

“Pity and anger welled up in us when we saw these respected, dignified religious leaders, who generally refrained from entertainment, forced to dance disco onstage,” he writes. “For their part, they gritted their teeth and tried not to acknowledge how ridiculous and pathetic their situation was. Forcing these absurdities on our clergy was a flagrant insult to them and to our faith, but there was nothing we could do about it.”

Out of sight are the reeducation camps, which the Chinese state has veiled in secrecy. Tahir spent time in an earlier prison camp years ago, although he scarcely mentions the torture he experienced there. (He is working on another book about those years.)

Instead, the fear in this book lies in the anticipation of what may come next. It manifests as an ever-present dread. When Tahir’s family finally escapes, he describes the physical exhaustion that came from living in anxious suspense for so long. Even here in the U.S., he avoids all communication with family and friends in China, because the state has punished Uyghurs merely for having correspondence abroad.

The narrative ends shortly after his family’s arrival in the U.S. But it gives clues to the question I brought to the book: How does he find sustenance after losing so much?

In part, it comes through elevating the stories of others, giving voice to the struggles of his people. In part, it comes through the practice of writing poetry. Tahir’s poems are tender and subtle. Some of them appear interspersed with chapters in the memoir. Another, from the website Words Without Borders, struck me with its beauty. From “The Past”:

In each person’s home was an old stove

with a flame no one dared to extinguish

In each person’s courtyard was a dark well

no one had the courage to uncover

In each person’s heart was a strange hope

no one was willing to speak aloud

Even in addressing world-historical events, he evokes the depth and complexity within every human heart. That’s something I respect.