An estimated 1 in 26 Uyghurs and other non-Han people in the Uyghur Region are imprisoned, making up a third of China’s total prison population

April 25, 2024, UHRP

A UHRP Insights column by Ben Carrdus, UHRP Senior Researcher, and Peter Irwin, UHRP Associate Director for Research & Advocacy

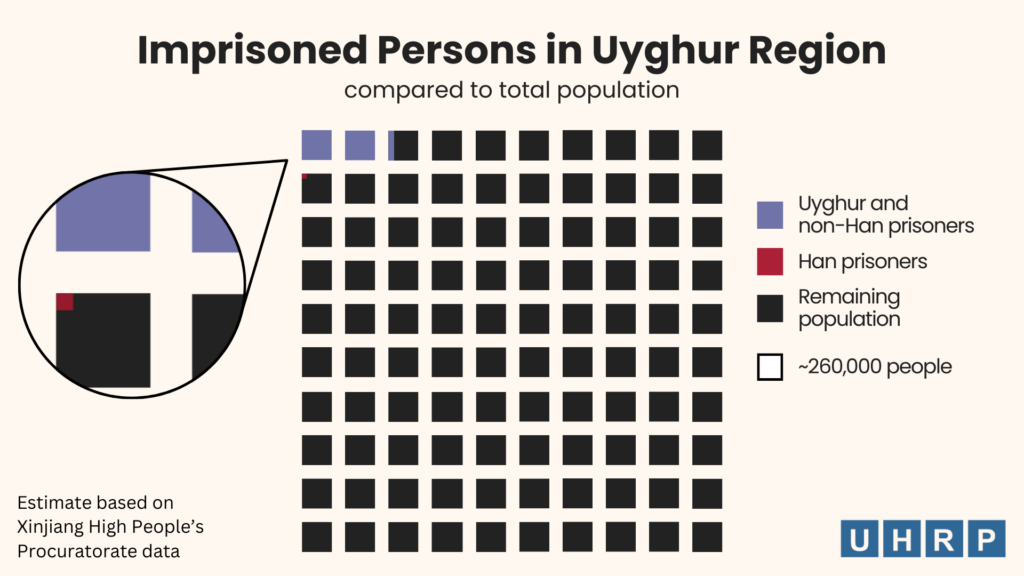

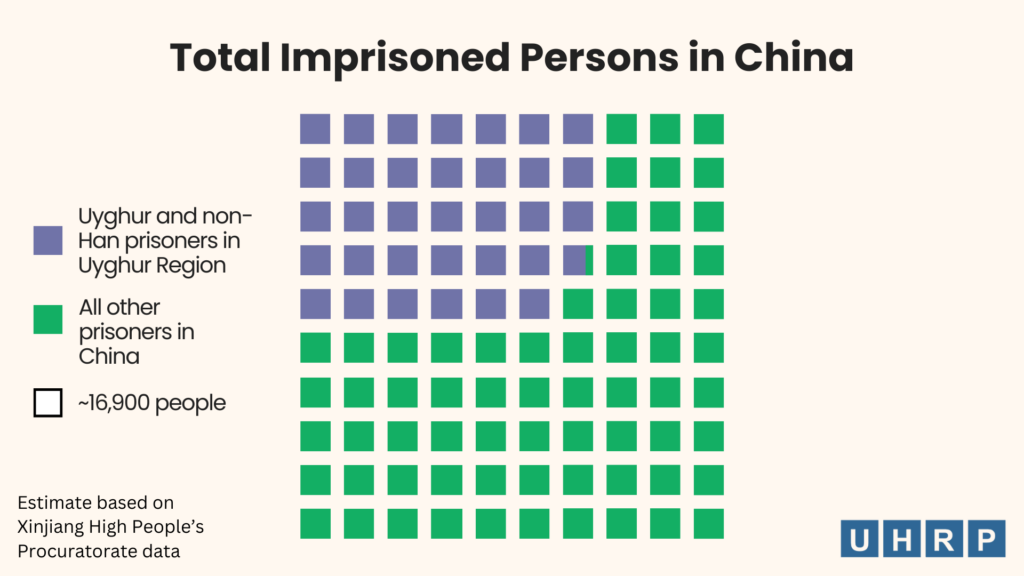

A new UHRP analysis of official figures1 indicates that Uyghurs, Turkic and other non-Han peoples in the Uyghur Region account for more than a third (34 percent) of China’s estimated prison population, despite making up only one percent of China’s overall population. When accounting for the total regional population, the Uyghur Region has the highest prison rate in the world at an estimated 2,234 per 100,000.

The prison population refers specifically to formal imprisonment under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice, and is separate from the unknown number of people still interned in the region’s camps and other forms of arbitrary detention.

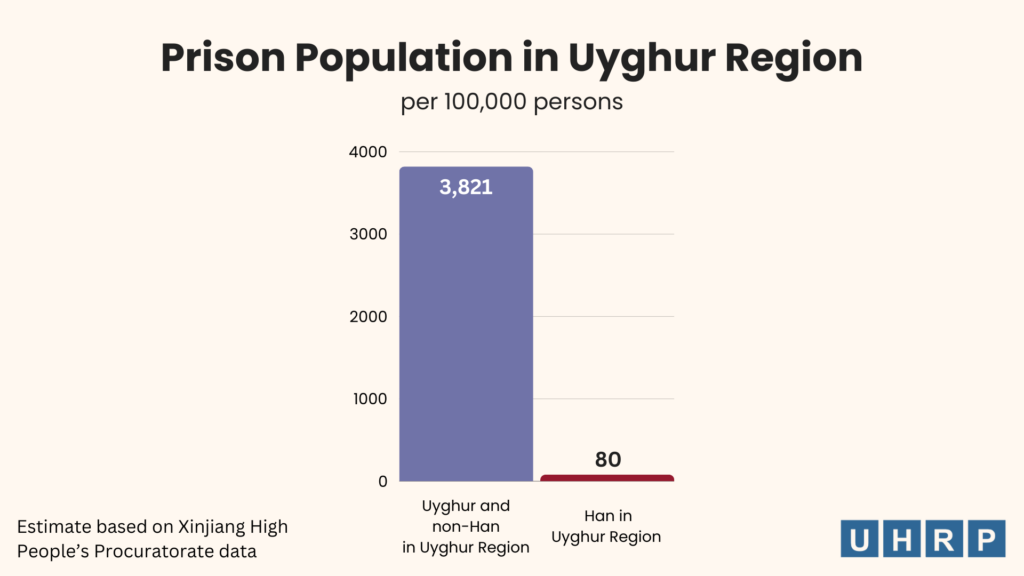

Statistics released by the state prosecution in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR)—known as East Turkistan to many Uyghurs—suggest that Uyghurs, Turkic and other non-Han peoples in the region are imprisoned at a rate of 3,814 people per 100,000.2

In comparison, Han people throughout China are estimated to be imprisoned at a rate of 80 per 100,000. In other words, Uyghurs and other non-Han people in the Uyghur Region are estimated to be imprisoned at just over 47 times the rate of Han people.

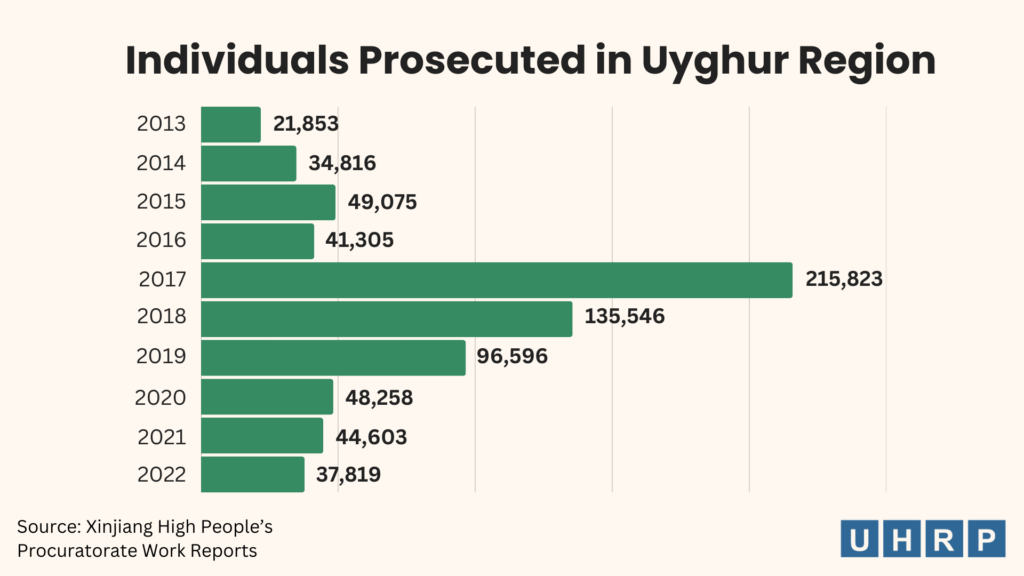

These estimates are based on official statistics for the six years up to 2022, which included the peak of the “strike hard”3 campaign and which show a cumulative total of 578,645 criminal prosecutions from 2017 to 2022.

Yearly prosecution statistics are usually published in the regional procuratorate’s annual work reports early in the following year; however, they are not included in the report for 2023, possibly because of previous coverage and analysis of the figures by Human Rights Watch. Similarly, in 2019 the regional High People’s Court stopped publishing breakdowns of prison sentences after Human Rights Watch reported the official statistic that 87 percent of all sentences in the region were for a minimum of five years.

However, even without knowing the precise number of prosecutions since 2022 or sentencing breakdowns since 2019, UHRP still estimates that the overall prison population today likely remains as high as it was during the peak of the strike hard campaign. Given the high prosecution numbers for 2018 and 2019 amid the continuing strike hard climate, it is reasonable to assume that sentencing patterns in those years remained every bit as harsh as they were in 2017. For instance, an analysis of 19,014 cases contained in the Xinjiang Victims Database with information on sentencing from 2016 to 2024 indicates an average sentence of 8.5 years.4

While many of those sentenced in 2017 and beyond should have been released by the time of writing in April 2024, they are likely to have been replaced by those prosecuted since 2022, leaving the net prison population largely stable.

There are good reasons to suppose that the imprisonment rate may be considerably higher than UHRP’s estimate. The statistics released by the Xinjiang procuratorate do not include those already in prison in 2017 and who may still be serving sentences, nor do they include people held in pre-trial detention, or people still arbitrarily incarcerated in the Uyghur Region’s concentration camps. In addition, it isn’t clear whether the official statistics include prosecutions by the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC or Bingtuan) procuratorate, which could add several tens of thousands of prosecutions to the total.5

A study of leaked official documents by the Associated Press in 2022 showed that at least 1 in 25 Uyghurs in a single county in the Uyghur heartland had been sentenced to prison on charges relating to terrorism, separatism or religious extremism. The AP study used information from Konasheher county (Ch. 疏附县) where the population is overwhelmingly Uyghur: according to official statistics from 2020, Uyghurs were 98 percent of the population. UHRP’s analysis provides a similar figure for the imprisonment rate, but bases it on population figures for the entire region, and includes other non-Han peoples.

These dramatic increases in the number and length of prison sentences in the Uyghur Region should not be interpreted as a reflection of increased criminality among Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples. Instead, as noted in UHRP’s recent report on women religious figures in East Turkistan, there is “a remarkable, indeed shocking, lack of proportionality between crime and sentence” when Uyghur cases go through the Chinese courts.

Based on analysis of leaked government documents, UHRP’s report details how, for example, Ezizgul Memet studied the Quran with her mother for three days in 1976 when she was five or six years old, for which she was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2017. Tursungul Emet did the same in 1974, and was sentenced to 11 years. Aytial Rozi studied the Quran and taught it to a group of women between 2009 and 2011, for which she was sentenced to 20 years in prison. In a single county in Kashgar, Human Rights Watch documented that 99 percent of all prison sentences in 2017 were for a minimum of five years, while the average sentence was 9.2 years. That is why prisons in the Uyghur Region are full and getting fuller.

It is already known that Uyghurs are far more likely than any other demographic in China to die in prison. What isn’t known is how many are being “judicially” executed. Statistics on death sentences are a state secret in China. But seeing as Uyghurs have been given life sentences for the most innocuous “offences,” it is highly likely that executions are distressingly commonplace.

Given the tight restrictions and manipulation of official information coming out of the Uyghur Region, UHRP has taken these official statistics at face value for the purposes of this analysis. A previous UHRP Insights article described the frustrations of researching human rights issues in China. The CCP’s deliberate withholding of crucial information about the number of prosecutions and sentencing patterns in the Uyghur Region is another case in point, and every year, transparency is reducing.

Our analysis represents our best estimation of the current prison rate in the Uyghur Region, but would require further transparency from the Chinese government to be even more authoritative.

This lack of transparency is frustrating for human rights researchers at their desks in Washington, DC: so many careful assumptions have to be made. But for the families of the hundreds of thousands of people imprisoned in East Turkistan, many not even knowing where their loved ones are imprisoned or even if they’re alive, assumptions is all they have.

UHRP acknowledges the advice and assistance of experts who wish to remain anonymous. Any remaining errors are the fault of the authors alone.

Statistical Analysis

The following text provides a guide to how UHRP arrived at its estimates on imprisonment rates in the Uyghur Region on the basis of the Xinjiang High People’s Procuratorate’s statistics. Below are the main outcomes of our analysis:

- Uyghurs, Turkic and other non-Han people’s account for 1% of the overall population of China, but comprise 33.7% of the national prison population;

- The world’s highest known national rate of imprisonment is in El Salvador, with a rate of 1,086 per 100,000;

- Uyghurs and other non-Han people in the Uyghur Region are imprisoned at an estimated rate of 3,814 per 100,000, slightly more than 3.5 times greater than El Salvador’s imprisonment rate;

- In comparison, Han people throughout China are imprisoned at an estimated rate of 80 per 100,000, 47.1 times below the estimated rate for non-Han people in the Uyghur Region;

- UHRP estimates that 1 in 26 Uyghurs and other non-Han people in the Uyghur Region are currently imprisoned; UHRP’s estimate further equates to 1 in 17 Uyghur adults in the region currently imprisoned.

Statistics on the number of prosecutions in the Uyghur Region published by the Xinjiang High People’s Procuratorate (the agency that prosecutes criminal defendants in the courts) and first compiled and analysed by Human Rights Watch, show that between 2017 and 2021, a total of 540,826 people were criminally prosecuted by the courts in the Uyghur Region, and another 37,819 were prosecuted in 2022, giving a total number of 578,645 prosecutions from 2017 to 2022. This number is separate from the numbers of civil and administrative prosecutions;

The conviction rate in Chinese courts throughout China in 2022 was 99.975%, which suggests a total of 578,500 guilty verdicts in East Turkistan over the six-year period up to 2022 (the conviction rates in previous years were only marginally lower than the rate in 2022 and unlikely therefore to be statistically significant);

There is a likelihood that a handful of cases were dropped by the state prosecution once they came to court, but based on evidence from national figures, this number is also not likely to be statistically significant;

Possibly not all of the estimated 578,500 people prosecuted and convicted were imprisoned—a proportion may have been given non-custodial sanctions. However, given the effects of the prevailing “strike hard” policies across the criminal justice system, UHRP believes that this number is also not likely to be statistically significant;

A key indicator for the near-universal imprisonment of the estimated 578,500 convicts is that 87% of those convicted in 2017—when a “strike hard” campaign was in full swing—were given a minimum prison sentence of five years, according to the regional High People’s Court’s statistics (the court stopped publishing statistics on sentence length after this figure was widely reported);

As also noted by Human Rights Watch, 99% of inmates in a Uyghur-majority county in Kashgar Prefecture were given prison terms of five years or longer in 2017, with an average of 9.2 years, according to leaked statistics;

Furthermore, a UHRP analysis of 19,014 cases in the Xinjiang Victims Database between 2016 and 2024 indicates an average prison sentence of 8.5 years;

UHRP therefore takes the figure of 578,500 as a proxy for the number of prisoners in East Turkistan in 2022, and contends that the figure likely remains the same or even higher today. The estimate of a prison population of 578,500 does not include those already in prison in 2017 or those in pre-trial detention (the lines between pre-trial detention and administrative detention in a concentration camp appear to be blurred);

In addition, it is unclear whether prosecution statistics include cases in the ongoing process of transferring camp detainees straight to prison as some evidence suggests that the camps are being phased out. Nor is it clear whether the statistics include prosecutions from the Bingtuan’s courts—the annual Xinjiang High People’s Procuratorate work reports barely mention the Bingtuan;

The official population of the Uyghur Region in 2021 was 25,890,000; therefore, the estimated imprisonment rate for the region in 2021 (578,500 as a proportion of 25,890,000) was 2,234 per 100,000 of the region’s overall population;

To correct for ethnicity, UHRP first subtracted the estimated prison population for East Turkistan from the estimated total prison population for all of China (1,690,000 – 578,500), leaving a total of 1,111,500 prisoners outside of the Uyghur Region in China;

Overall, as of 2021 China had an estimated imprisonment rate of 120 per 100,000 ((1,690,000 ÷ 1,412,175,000) x 100,000);6 however, if the estimated prison population in the Uyghur Region is excluded from the national total (minus the population of the Uyghur Region), the imprisonment rate for the rest of China is 80 per 100,000 (1,111,500 ÷ (1,412,175,000 – 25,890,000) x 100,000);

Assuming that Han are imprisoned at the same rate in East Turkistan as estimated for the rest of China7—i.e., 80 per 100,000—then:

With an official “ethnic minority” (non-Han) population in the Uyghur Region of 14,932,200 in 2020, the remaining Han population would be 10,957,800; therefore, the number of Han prisoners in the region can be estimated to be 8,766 (that is: (10,957,800 ÷ 100,000) x 80);

When 8,766 is subtracted from 578,500 as the estimate for the total number of prisoners in the region, a figure of 569,734 remains, representing UHRP’s estimate for the total number of non-Han prisoners in East Turkistan in 2022 (and which likely remains similar or higher today);

The imprisonment rate for non-Han people in East Turkistan would therefore be 3,814 per 100,000 (569,622 as a percentage of 14,932,200 is 3.8%, or 3,814 per 100,000), or 47.1 times the imprisonment rate for Han people across China;

The non-Han population of the Uyghur Region is 14,932,200, which is equivalent to 1% of the total population of China (14,932,200 as a percentage of 1,412,175,000); and the non-Han prison population of the Uyghur Region is 33.7% of China’s overall prison population (that is, 569,843 as a percentage of 1,690,000);

UHRP estimates that China’s Han prison population is 60.4% of the national total, or 1,020,231 people ((1,111,500 x 0.91) + 8,766 = 1,020,231);

The official population of Uyghurs in East Turkistan in 2022 was 11,774,538, which suggests an estimated Uyghur (not including other non-Han peoples) prison population of 449,080 people (11,774,538 ÷ 100,000 x 3,814);

The overall imprisonment rate for non-Han people in the region equates to 1 in 26 people currently in prison; with around 7,720,000 Uyghur adults in the region, it can be further estimated that the imprisonment rate for adult Uyghurs in East Turkistan is 5,817 per 100,000, or slightly more than 1 in 17 Uyghur adults (449,080 as a percentage of 7,720,000 million = 5.8%; 100,000 ÷ 5,817 = 17.2).