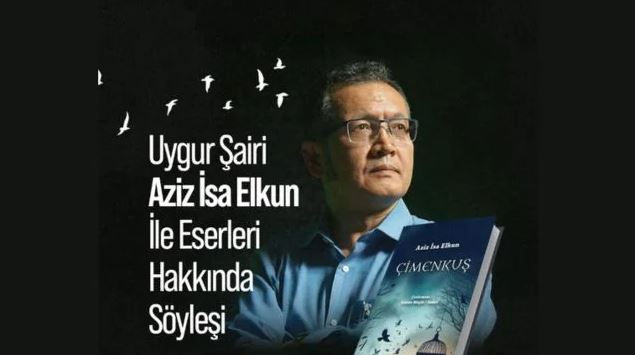

Front cover of “Çimenkuş,” a new volume of Uyghur poetry written by Uyghur exile Aziz Isa Elkun, and translated for a Turkish audience ( photo used with permission of Ömca Astana Yayinlari publishing house).

An anthology of poetry by Aziz Isa Elkun is published in Turkish. It is much more than a literary event: it calls fellow Turkic peoples to support the victims of a genocide.

by Ruth Ingram

10/14/2024, Bitter Winter

“Your poems will soar

In the blue sky where you belong

Because the sky is free, unlike you

It can visit you through your narrow window

When you feel sad…

Chimenqush, I know you were never afraid of the seasons

I know no one can cheat you

You will return one day

You will come back next spring

Holding a bunch of flowers in your hand.”

(Excerpt from “Chimenqush—a flower bird” by Aziz Isa Elkun November 1, 2018, London)

Chimengul Awut, beloved Uyghur poet, in whose honor this poem was written, was arrested, and detained for five years during the mass roundups and imprisonments of Uyghurs by the Chinese government in 2017, for her work in the Kashgar Uyghur Publishing House. Its author, Uyghur exiled poet, Aziz Isa Elkun has included this tribute to her in his recently launched poetry anthology, using her pen name “Chimenqush” (Turkish, Çimenkuş) meaning “flower bird” as its title.

Awut’s parting gift to her son as she was taken away had been a line hastily scribbled on her WeChat social media page, “My dear son, please don’t cry. The whole world will cry for you!”

Tragedy, triumph, and the power of the human spirit are brought into sharp focus in Elkun’s 54 carefully chosen works translated from the original by Istanbul-based Uyghur exile, Amina Wayit Sedef and published by Ömca Astana Yayinlari Publishers in Türkiye in September 2024.

More than 50 Turkish writers, academics and poets joined members of the World Uyghur Writers Association and diaspora Uyghurs from Istanbul, gathering under the banner of the Turkish Writers’ Association to support Uyghur poet Aziz Isa Elkun in celebrating his debut poetry compilation, now available in translation for the wider Turkic world.

Launching his work for the first time in the Turkish language, the London-based Uyghur exile hopes to “capture the trauma of separation and the enduring suffering of an exiled Uyghur poet’s inner soul and sorrow” for a Turkish audience. Speaking to “Bitter Winter,2 Elkun said that his new anthology was a rallying cry to the Turkic world to stand with Uyghurs “during one of the darkest periods in their history.”

Addressing a packed hall Elkun urged them to use their pens to highlight the Uyghur plight.

“We Uyghurs stand at the precipice of existence, our being is threatened. But you, with your pens, hold the power to illuminate our struggle. Write for us, for our freedom, for our dignity. Remember, the pen has always been mightier than the sword.”

The anthology weaves messages of love, longing, pathos, and tragedy to capture his own personal journey of exile and the pain of separation from his family and his homeland. Through vivid and evocative language, the poems reflect the anguish of living away from his people and the broader tragic fate that the Uyghurs have faced in recent decades, highlighting themes of loss, resilience, and the enduring connection to one’s cultural roots.

The idea of a volume in Turkish came originally from the translator herself who had approached Elkun two years ago with her idea for this project. She told “Bitter Winter” that the sentiments expressed by Elkun reflected the deep emotions felt by every exiled Uyghur. “This is why I love reading his poems and what drove me to translate his works into Turkish,” she said. “His poetry expresses a deep love and homesickness for our homeland, conveying his despair and sadness over the situation there. In his poems, he reflects on his childhood, highlighting how much he misses the place where he grew up. He also writes about his desire for freedom, believing that a bright day will surely rise after the darkness.”

Elkun’s hope through this treasury of verse is that Turkish readers will gain a deeper understanding of the Uyghur exile experience. Through his poem “Roses” he urges readers to reflect on the role the wider Turkic world has played in offering support to its suffering brethren, and calls for greater solidarity “as China commits genocide on my people.”

Elkun dedicated “Roses” to the Uyghurs arrested and detained in the Chinese Communist Party’s mass clampdowns and round ups in 2017.

“Roses”

Aziz Isa Elkun 2021, London

It’s a morning bright with sun

Another new day has started

I count, altogether twenty-two autumns

And winters have passed in exile

And I don’t know how many years remain

Before I return to the place where I belong

To the earth that my forefathers made home

I can feel the sorrow in myself

My soul shivers; it’s cold

I inherited it all from my father

Whenever the memory of the disappeared homeland

Returns and occupies my mind

It inspires me to be human with dignity

Able to call for the survival of a lost nation

Able to appeal for mercy and love

From the world

Again and again

The place where I was born

Has turned into a heap of ghostly relics

It only exists amongst the non-existence

In this world full of selfishness.

I am sitting in a garden chair

Trying to enjoy the warm sun for a minute

But it is quickly covered by the rushing clouds

A steaming cup of coffee evaporates my gloom

I am still struggling to feel myself

Believing that better days will come after tomorrow.

One day life will smile on us

Even on the man who writes these lines

Although he lost everything

Traveling on the road of no return

And lived a second life

He is still a hostage to that place

He lives with constant fear

The monster has left countless stains

It has pierced me with needles

But still I call for justice for those

Who have suffered more

But my spirit is still fighting

My hope is still alive

Each time I find new courage

It brings the joy of a smile

Although it’s autumn

My garden leaves are still green

The first rose I planted three years ago

To mark my father’s destroyed grave

The second rose I planted

On Mother’s Day last year

The third rose I planted for the unknown Uyghurs

Who survive inside the camps

My roses are blossoming with hope

Singing a song of freedom

Without waiting for the spring

They remind us

How beautiful it is to be alive

To live in peace in our beautiful world.

Ruth Ingram is a researcher who has written extensively for the Central Asia-Caucasus publication, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, the Guardian Weekly newspaper, The Diplomat, and other publications.