The eleven-year confinement of Uyghurs in criminal cells violates UN detention standards and fundamental human rights, while their treatment defies international protections against arbitrary imprisonment.”

Latief U Zaman Deva*

Kashmir Times, November 7 2024

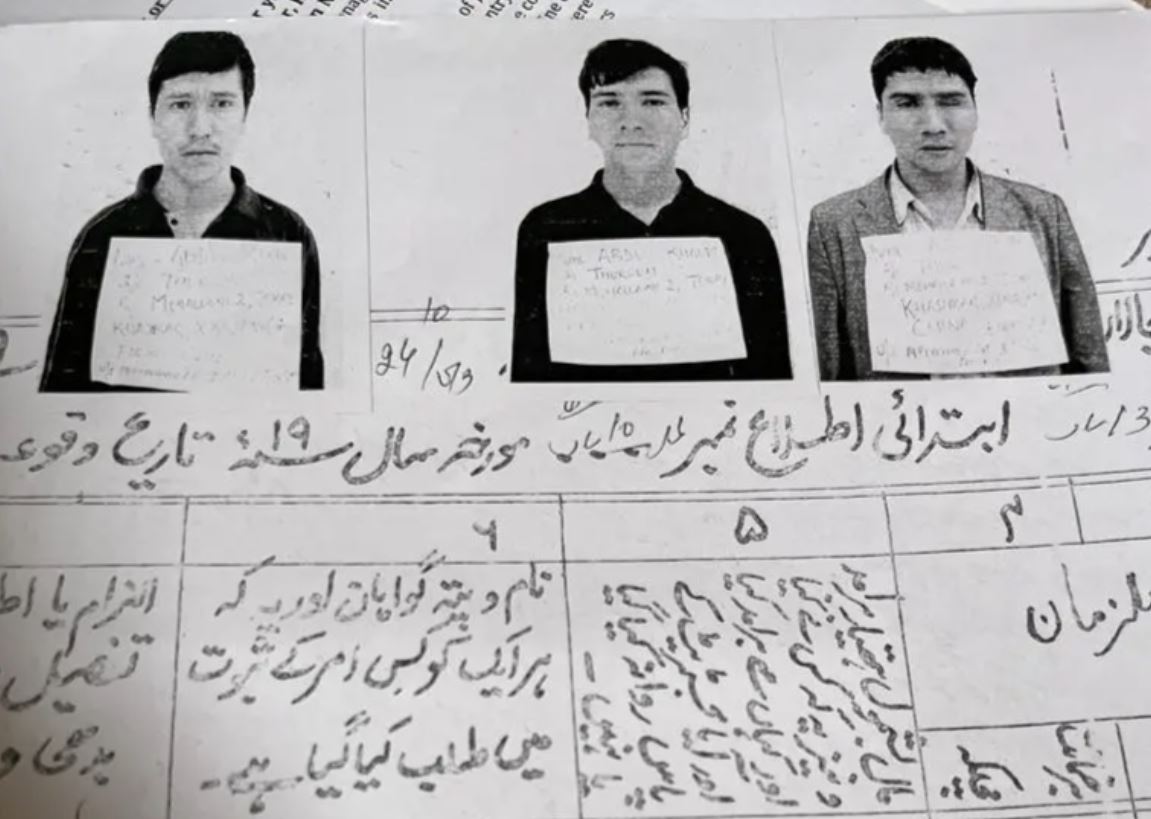

The fear of persecution compelled three Uyghur siblings, Abdul Salam, Adil, and Abdul Khaliq, to flee the Xinjiang province in China (formerly Turkistan), cross the Indo-China border, and enter Ladakh in the summer of 2013.

Chinese government’s systematic and unabated persecution of the Uyghur minority in the Xinjiang province includes identity-based restrictions, mass arbitrary detention, pervasive surveillance, forced sterilization, forced labour, and forced assimilation – actions that constitute crimes against humanity and potentially even genocide under international law.

Dreams to Freedom Dashed

The three brothers decided to flee after some of their relatives were forcibly put in mass detention centres. But the dreams of freedom were short-lived.

As soon as they crossed the borders, they were arrested in Sultan Choskur by Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) guarding the Line of Actual Control between China and India.

After enduring two months of interrogation, the ITBP handed over the three foreigners to the local police, who registered a case against them for crossing the border unlawfully without travel documents. They were then produced before the Judicial Magistrate Ist Class Nobra Disket, District Leh (Munsiff).

Unending Tribulations

The trial resulted in a one-and-a-half-year sentence award. But their ordeal did not end there. Instead of releasing them for grant of asylum in India or facilitating their travel to countries like Turkey or Malaysia, which welcome the Uyghur refugees, the J&K Public Safety Act 1978 was invoked to keep them incarcerated. They remained detained, for over a decade since they were first jailed.

The PSA is a controversial law under which an accused could be detained for up to two years without trial. Every time their detention term expired, the authorities issued new detention orders under the same law.

First lodged in Jammu’s Kot Bhalwal Jail, the three have since been shifted to Karnal jail in Haryana, and completely forgotten about long after they served a sentence as convicts. The ordeal reflects nothing but a travesty of justice.

The three detainees are bonafide residents of Kashghar Kargilik, Xinjiang, where they felt an existential threat and decided to flee but they were unaware of the world beyond their home. They could not speak English, Urdu, or any other language spoken in the sub-continent. In the last decade, they have picked up a mix of Urdu and Hindi from other jail inmates.

Lassu notes that the Uyghurs have been held in custody for over 11 years in a foreign country, making it impossible for their families in China to know about their whereabouts or reach them. Additionally, he is worried about their ability to withstand the harsh climatic conditions and unfamiliar vegetarian diet in a prison in the plains, as well as the psychological toll of being confined in cells designed for convicted criminals rather than detainees.

Lassu has petitioned the Jammu and Kashmir government to have the Uyghur prisoners transferred back to Jammu, Srinagar, or Ladakh, which would be more conducive to their cultural and climatic needs. He argues that this is necessary to prevent further harm and potential psychological disorders resulting from their current detention conditions.

Persecution of Uyghurs

The persecution of the Uyghurs in China has been widely documented by human rights organizations, which have raised concerns about human rights abuses, forced disappearances, crimes against humanity, and acts of genocide. The Chinese government’s efforts to alter the demographic profile of Xinjiang and other historically non-Chinese regions are seen as part of a broader campaign of forced assimilation.

The Uyghurs are a Turkic ethnic minority group of around 12 million people who are culturally, linguistically, and ethnically homogenous with the central Asian nations, particularly Turkey.

China has long been wary of the diversity in the regions it has occupied, such as East Turkestan (invaded and occupied on December 22, 1949) and Kashgaria (occupied in 1884). Instead of embracing this diversity for greater cohesive integration, China has settled large numbers of Han Chinese people in these regions to strengthen its claims over a “Greater China.” By altering the ethnic makeup of historically non-Chinese regions like Xinjiang and Tibet through Han Chinese settlement, China is cementing its control and solidifying its territorial ambitions.

Human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have repeatedly raised concerns about China’s abuses against the Uyghurs, including forced disappearances, crimes against humanity, and acts of genocide. They have also condemned China’s establishment of what are effectively prototype concentration camps, euphemistically called “vocational skills training centers.”

The systematic persecution and forced assimilation of the Uyghurs by the Chinese government demonstrates its intolerance for ethnic and cultural diversity within its claimed borders, and its willingness to resort to extreme measures to homogenize these regions under Han Chinese dominance.

International Laws and Conventions on Refugees

Under Article 51 of the Constitution of India, the Indian State is envisioned to endeavour to promote international peace and security, foster respect for international law and treaty obligations, and encourage the settlement of international disputes by arbitration.

Refugee law is part of international Human Rights Laws. United Nations has long before adopted a convention relating to the status of Refugees in 1951 and the Protocol in 1967.

One of the predominant characteristics of the convention is “non-refoulement” which in bare words would imply that “no State shall force a refugee to return to the territory where his life and freedoms are threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, political group or political opinion … … ..”

An advisory opinion by UNHCR 2007 on extra-territorial application of non-refoulement obligations mandates the binding character of the said principle even on those States, who aren’t party to the 1951 Convention/1967 Protocol. Further, under Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the right to seek asylum for such refugees is protected.

In pursuance of Article 37 of The Directive Principles of State Policy under the Constitution of India, these directives are “fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws” irrespective of the chapter (Part IV) being non-enforceable by the courts.

The fundamental rights in their entirety are available to Indian citizens but an exceptional dispensation is explicit whereunder all persons including foreigners are entitled to the Right to Equality & Right to Life.

What Must Be Done

The laws envisage central and the Union Territory governments of J&K and Ladakh to shift the three Uyghurs to Srinagar/Jammu or Ladakh, followed by their release and grant of asylum, should they seek it. In case, they opt to move to another friendly country, their travel to that respective country should be facilitated.

The principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits the return of refugees to persecution, must be upheld as sacrosanct under international law.

Disregarding non-refoulement undermines the critical protections afforded to vulnerable displaced populations seeking sanctuary.

Any individuals or entities that facilitate the detention or deportation of refugees in violation of this fundamental tenet should be held accountable as their actions contravene established international laws and norms of humanitarianism and human dignity.

*The author is IAS (Retd), former chairman of J&K PSC & an Advocate at Srinagar.