Leaked Chinese government records show Beijing’s systematic reprisals against Uyghur reporters working for a news organization that is now in the Trump administration’s crosshairs.

The documents include a list of names with addresses, professions, phone numbers and other private details of 42 “sensitive and special” people who had allegedly been in “close contact” with Uyghur journalist Shohret Hoshur, 60. Hoshur, who escaped China in 1994, has been a reporter for Radio Free Asia (RFA) since 2007. Security officers needed to “pay close attention” to people who were once in Hoshur’s orbit, the document said, noting that one person, an author, had been “dealt with by the public security authorities on political suspicion.”

As a U.S.-based reporter for RFA, Hoshur has covered the Chinese government’s repressive policies against Turkic people in Xinjiang, including the mass internment of hundreds of Uyghurs — abuses that “may constitute crimes against humanity,” according to the United Nations. Hoshur’s deep knowledge of the region and extensive contacts have allowed him to gather exclusive information from police officers and other confidential sources on the ground. At the same time, his reporting has ignited the ire of Chinese authorities, who have accused him of encouraging terrorist acts and allegedly vowed to retaliate against Hoshur’s extended family and friends.

The records from the public security bureau of Tekes county, in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, were obtained by China researcher Adrian Zenz. They were shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists as part of the China Targets investigation into Beijing’s repression of dissidents and minorities living overseas. ICIJ found that Chinese authorities routinely pressured family members of activists and members of oppressed minorities who fled China to exert control over the diaspora.

“These documents show the importance of RFA reporting, and the extreme concern that their reporting has prompted within Xinjiang’s domestic security agencies and therefore its political leadership,” said Zenz, director of China studies at the Washington, D.C.-based Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

Despite RFA’s role in exposing China’s human rights abuses, the U.S. government recently canceled funding for RFA’s parent entity, U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), effectively dismantling the news organization. RFA was launched in 1996 to provide uncensored news coverage of authoritarian regimes, including China, and reached a weekly audience of nearly 60 million people worldwide. But in March, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order terminating a $60 million grant for the agency, which led to hundreds of reporters being laid off as well as the closure of its Tibetan- and Uyghur-language news services and other programs.

Vowing to implement the executive order, USAGM senior advisor Kari Lake said in a statement that the agency planned to reduce the outlets under its umbrella and their associated staff due to alleged mismanagement and financial irregularities. USAGM did not respond to ICIJ’s request for comment about the implications of the cuts for RFA and its journalists.

Hoshur is not the only journalist whose friends and family members have been affected by working for RFA. Chinese authorities have imprisoned or harassed more than 70 family members of seven of the 22 RFA journalists assigned to the Uyghur news service as a result of their reporting, RFA reporter Gulchehra Hoja recently told advocacy group Reporters Without Borders.

“It is clear that the authorities are considering the way in which RFA exposes their rights-violating policies to be a major threat to their political and regime security,” Zenz said.

‘Playing into the hands of President Xi Jinping’

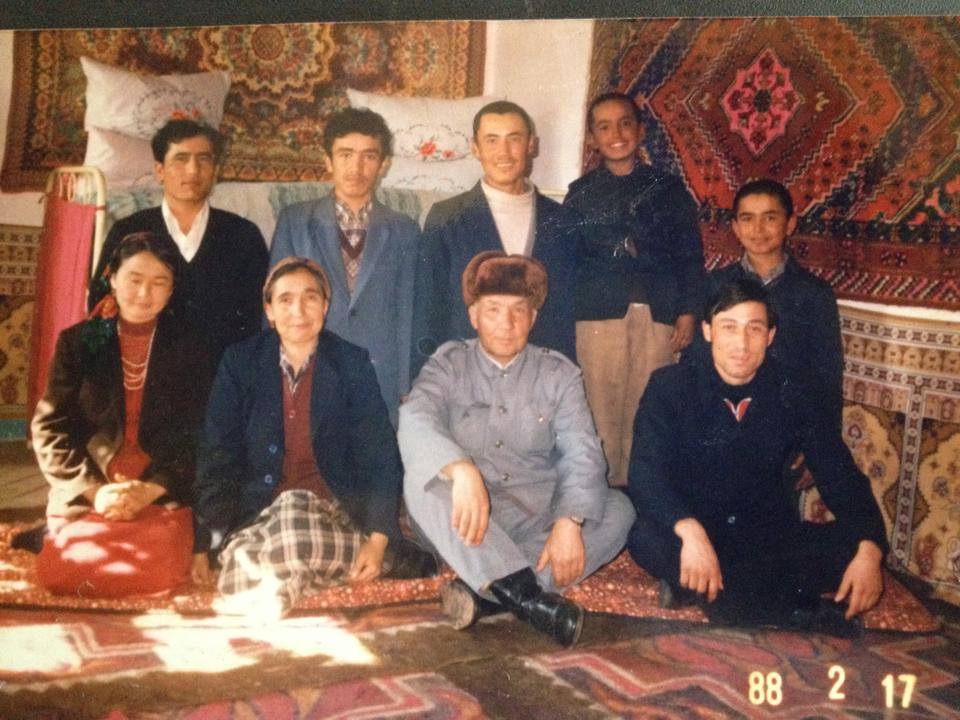

When Hoshur first read the list of acquaintances under surveillance by Xinjiang officers, he was surprised to see the names of his college friends from decades earlier.

“I recognize all of them,” Hoshur told ICIJ of the classmates he said he hasn’t seen in over 30 years.

Despite the officers’ allegations, Hoshur remembered many of those acquaintances being “extremely quiet and cautious about anything political,” he said. “They avoided social events and kept a low profile. There were even a few who were openly loyal to the Chinese Communist Party, and yet they were also targeted.”

Hoshur said that four of his siblings, including three of his brothers — a cosmetics store owner, a merchant who ran a butcher shop and a farmer — as well as their spouses, have been missing for eight years and were likely sentenced to more than 15 years in prison on spurious charges. He believes his journalism is the reason for their detention because the authorities, who secretly monitored their calls, “repeatedly pressured them to persuade me to stop my work, warning that otherwise they would face consequences,” Hoshur said.

Alongside police bulletins and internal security guidelines reviewed by ICIJ, the government documents provide new evidence of how Chinese authorities, seeing the media outlet as a threat to the Chinese Communist Party’s rule, have strictly monitored RFA reporters abroad and harassed their families and acquaintances.

Some U.S. lawmakers and human rights advocates have criticized the decision to end funding for RFA, arguing that closing the organization and its sister company, Voice of America, is a boon for China’s authoritarian government. “By letting RFA go totally dark at this crucial moment, the U.S. government would cede the information space to China, playing into the hands of President Xi Jinping,” RFA CEO Bay Fang wrote in a New York Times editorial. “If RFA is silenced, the official narratives espoused by dictators and despots may go unchecked and unchallenged.”

An editorial in The Global Times, the Chinese state mouthpiece, praised the funding cuts to VOA and RFA, saying that their “primary function is to serve Washington’s need to attack other countries based on ideological demands.”

A price for journalism

Hoshur, who worked for a broadcaster in his native Xinjiang, fled China in 1994 after he wrote two articles about Beijing’s oppression of Uyghurs, which the government’s propaganda department labeled subversive. Wanted by the authorities, he bought a fake passport and fled first to Pakistan, then to Turkey and later to the U.S., where he became a citizen. While in exile, he has continued to expose Chinese policies affecting his community.

As Uyghurs listened to his reporting on RFA broadcasting, “authorities wasted little time in making it clear to my family — and to me — that they would one day pay a price for my journalism,” Hoshur told the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China in 2015.

At the time, a spokesperson for the Chinese government denied retaliating against Hoshur’s family and dismissed the accusations as “totally baseless.” But the leaked records show that in 2014, Xinjiang authorities drafted the list of Hoshur’s acquaintances as part of a government “plan on preventing, controlling, and combating Radio Free Asia’s collusion with domestic organizations.”

According to the plan reviewed by ICIJ, authorities believed RFA reporters were responsible for “spying on and hyping up information on sensitive and hot cases involving Xinjiang.” As a consequence, a government unit was put in charge of investigating “the number of local people who have colluded with Radio Free Asia, find out their true identities, historical collusion activities, and current performance one by one, and include them in key persons or special groups as appropriate, and implement control measures.”

That year, as officers appeared to implement the plan, Chinese authorities imprisoned Hoshur’s three brothers for “violating state security laws” and allegedly “leaking state secrets” after discussing the sentencing of one of the brothers in a phone call with the reporter — allegations that Hoshur dismissed as false.

Shohret Hoshur with a colleague in the Radio Free Asia newsroom in 2025.

Hoshur later denounced the injustice against his family in interviews with the media and with advocacy groups, as well as at the commission hearing.

Two of his brothers were released after 18 months of detention, partly due to the U.S. government’s involvement in the case, Hoshur said. The brothers were detained again in 2018 along with Hoshur’s other siblings and mother. While his mother was also later released, Hoshur said that at least 10 of his close relatives are still in prison and that he is “unsure of their current sentences.”

In 2018, when RFA and VOA covered the mass internment of Uyghurs and other state-sponsored abuses, Xinjiang police officers routinely monitored the news sites and flagged articles deemed to be subversive, leaked police bulletins reviewed by ICIJ show.

“On June 16, 2018, Radio Free Asia News, an overseas site, published a news article saying that the situation in Xinjiang is a matter of concern,” an officer wrote in a report two days after the article was published. “The above-mentioned situation has been defined as an attack by hostile forces outside the country.” The officer submitted the report to his superiors.

According to Adrian Zenz, the authorities recorded “in great detail RFA reports about Xinjiang that are critical of state policies or expose aspects of the atrocities,” indicating “the importance of RFA reporting.”

Early this year, RFA filed a lawsuit against the U.S. government and USAGM to reinstate its funding, arguing that the termination violated federal law. Despite its reduced staffing, the outlet continues to provide limited news coverage on its website in nine languages, including Mandarin and Cantonese. The case is ongoing.

For Uyghurs both abroad and in the homeland, the shutdown of RFA’s Uyghur service means losing “the only bridge they had to communicate with each other,” Hoshur said. “Uyghur activists have lost a critical weapon in their resistance against China’s authoritarian regime.”