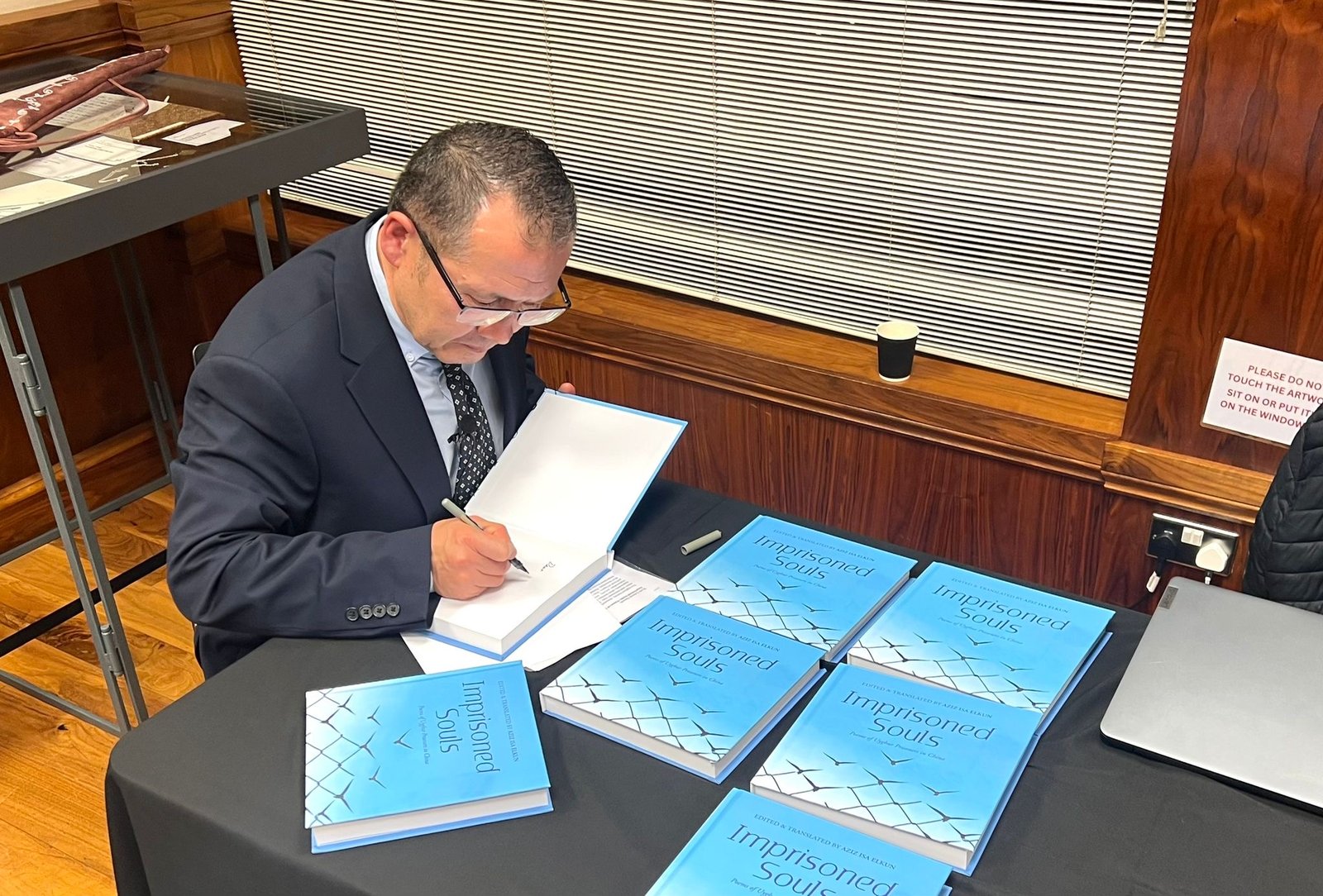

Aziz Isa Elkun addressing the book launch of “Imprisoned Souls” at the Yunus Emre Institute in London, December 16, 2025. Photo by Ruth Ingram.

A new anthology reveals the suppressed voices of Uyghur poets, most of whom are in jail.

by Ruth Ingram

Dec 26, 2025 Bitter Winter

“Pen, grant me faith to be yours alone.

Ignite in me a conscience fierce for all, if ever I write black as white.

Let the weight of shame ensure my fall.

When the poet sees those frozen in ice,

He pours his boiling blood to thaw them.

To grant others freedom, life’s worthiest prize,

He remains captive to his own desires.”

Writing in 1999 in this excerpt from his poem, “Pen and Poet,” Uyghur scribe Abduqadir Jalalidin knew the price his pen might one day have to pay. 21 years later, three years into a 13-year prison sentence, silenced for his craft, his scribbled lines, “No Road Back Home,” were smuggled out of his prison cell in 2020:

“Through cracks and crevices, I’ve watched the seasons change

For news of you, I’ve looked in vain to buds and flowers,

To the marrow of my bones, I’ve ached to be with you.

What road led here, why do I have no road back home?” (excerpt).

“Imprisoned Souls: Poems of Uyghur Prisoners in China” (Hertfordshire Press, 2025) is the culmination of UK-exiled Uyghur poet Aziz Isa Elkun’s five-year odyssey into the relentless suppression of Uyghur poetry and its authors, most of whom are enduring lengthy prison terms in their homeland. His mission to break the silence, crushing the muzzled authors, following the cultural pogrom unleashed in their homeland in 2016 by the Chinese state, has, he said, “haunted him daily.”

Speaking to “Bitter Winter,” he said, “This anthology is published at a critical moment, as the Chinese regime continues its relentless atrocities of genocide and cultural erasure against the Uyghur people. Born of over five years of urgent, emotionally demanding work, shaped by responsibility and deep personal loss, I hope it helps readers understand what these imprisoned poets wrote, and how brutally they were punished for their words.”

Leila Isa, daughter of Aziz Isa Elkun, reciting one of the poems from the anthology at the launch at the Yunus Emre Institute, in London, December 2025. Photo by Ruth Ingram.

By honoring 25 poets from the 500 or so intellectuals who have been detained, interned, or sentenced to long jail terms in the Uyghur region since 2016, Elkun hopes that “the soul of the Uyghur people will speak directly to the heart of the English-speaking world.” “Uyghur poetry has long been a lifeline for our language and a voice of resistance and hope, yet it has been relentlessly suppressed,” he said.

“Though silenced, their voices still speak to all who believe in human dignity and the freedom to write,” he added.

A brief roll call of some of those whose work has been selected by Elkun reveals a distressing catalogue of men and women, behind bars for loving their language, culture, freedom, and justice, or who have simply disappeared:

Abdurehim Abdullah—arrested Spring 2018–whereabouts unknown.

Perhat Tursun—detained January 2018—sentenced to 16 years—situation unknown.

Ablet Abdurishit Berqi—arrested Autumn 2016–sentenced to 13 years—current circumstances unclear.

Nurmuhammed Yasin Orkishi—February 2005, sentenced to 10 years. Whereabouts unknown.

Gülnisa Imin Gülkhan—arrested December 2018–sentenced 2019 to 17 years and six months for separatism. Current whereabouts unknown.

Ruqiye Abdullah—arrested Autumn 2017– current whereabouts unknown.

Sirajidin Rahman-arrested 202—sentenced to life imprisonment—whereabouts unknown.

Zohre Niyaz Sayramiye—September 2018 sentenced to 8 years— whereabouts unknown.

Dr Jennifer Langer, director of “Exiled Writers’ Ink,” a UK charity that encourages literary expression among exiled writers, speaking at the London launch of the collection on December 16, described the phrase “whereabouts unknown” as the most tragic eulogy for these carriers of the Uyghur language and soul. “We must be the voice for their stifled cries,” she said.

Uyghur poetry is replete with metaphor, tenderness and fury, passion and yearning. Enduring themes never far from the surface are the fate of the homeland and Uyghur nation, loss of freedom, separation, and unrequited love.

Berqi rails against the “occupiers” of his land in this excerpt from “The Confession of a Poem”:

“If you are going to blindfold me,

My soul will simply rebel against it.

My body will turn into words.

The blood in my veins will explode.”

Gulnisa Imin vents over “wounds that would not close,” the “bittersweet sorrow” and “blue scars of agony that remain,” and the “pitch black longing that consumed her” in “Eleventh Night: Your Voice Feels So Distant,” one of a stream of daily poems posted from December 2015 over Weixin, the only permitted Chinese social media platform, one hundred and one of which were captured by Elkun, a close friend in exile, and published online. She had written 345 of these before she was arrested in 2018, leaving her two children behind.

Aziz Isa Elkun (right) with Turgunjan Alawudun, President of the World Uyghur Congress. Courtesy of Hertfordshire Press.

In “Nameless,” a poem that surfaced in 2024 after her detention, she remains defiant, demanding no tears of sorrow, or “pale faces” for her sake. Her only request was for her “two stars,” whom she entrusted to the readers:

“For my sake, shower them with your love.

Let them grow in the same embrace I grew in.

Let them live with the love they deserve.”

The celebrated Uyghur poet Adil Tuniyaz, arrested with his wife Nezire Muhammad Salih in December 2017, laments the extinguishing of the Uyghur language in his piece “Let’s Cherish Each Other,” as he writes:

“Flowers scatter on the Uyghur language.

An elderly man gathers them carefully

Within the cradles of his eyelashes” (excerpt).

His deep love for his homeland was expressed in “The Moon’s Reply,” written before his arrest:

“My devotion remains eternal

The Motherland, my anchor, my soul.

I will drift above her always,

Shining, casting golden light.”

Ablet Abdurishit Berqi was condemned to prison for 13 years for admitting he was “on the side of blood that flows” and of “tears that fall”; for identifying his land as “the place where no camera ever reaches or even glances their way to remember their pain”; for demanding in December 2015 ( as the mass round ups of Uyghurs began) to know why the streets were empty and why the “hospitals” (a euphemism of detention during those dark days) were “overflowing” and “echoing with the sound of crying” (“Hospital”)—the question “seething” in his mind being the true identity of the doctor.

Sirajidin Rahman, whose recording studio became a hub for cultural preservation, translating rare films, collecting Uyghur folk tales and archived songs, dared to write about the Uyghur spirit “roaming wild in the desert” within a “vast sea of boundless possibility” but who are condemned to “endure the shade of hell” (from “The Shade of Hell” August 1999). For his outspoken “subversion,” he was given a life sentence in 2021.

Despite the trauma and tragedy, loss and separation, and daily reports from the Uyghur region of genocide, cultural erasure, and wide-scale injustice, Elkun refuses to be cowed.

“The Uyghur people have endured the darkest times and will continue to rise above oppression,” he writes in his book. “As long as they dream of a free homeland, the Uyghur spirit will never be extinguished. Their struggle for freedom will persist until they live freely in their own land, in dignity and peace. This book is not solely filled with sadness; it also carries love, hope, and optimism for the future. The poems within reflect the resilience and beauty of the Uyghur language, and I hope you find joy and inspiration in them.”

Ehmet Kibir, arrested in 2018 and sentenced in 2019, describes the “most dreadful fate” as living “without hope or courage.”

In his poem “Snow Lotus Blossom,” he says:

“If you stand beneath mountains, never looking up

If you fail to see orchids blooming in the desert

Morning will break without the warmth of sunrise

The Moon will drift veiled behind the clouds.

Know that you have a home upon this earth

Live with love for this vast, infinite land

Look, the snow lotus blossoms even in the cold

Even a drop of water holds a realm for life.”

Elkun continues, “I firmly believe that justice for the Uyghurs will prevail and that the imprisoned poets, who have been silenced for their words of truth and freedom, must be freed. Please, do not forget them,” he pleads, “be the voice for their silenced cries echoing from the depths of their prison cells.”

Ruth Ingram is a researcher who has written extensively for the Central Asia-Caucasus publication, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, the Guardian Weekly newspaper, The Diplomat, and other publications.