December 30, 2025, Uyghur News Network

by Mamatjan Juma

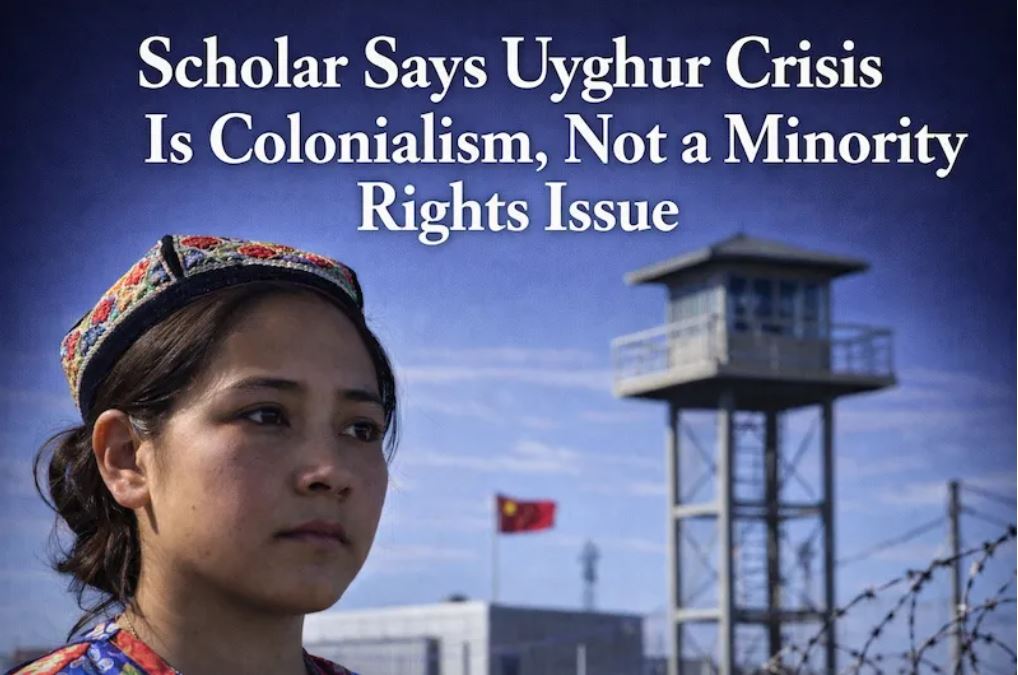

A Cambridge University Press study argues that describing Uyghurs as a “minority” obscures a colonial relationship dating back to China’s 1949 takeover of the region.

The research says focusing only on abuses since 2017 overlooks a longer history of demographic change, land restructuring, and political control.

The scholar argues that categorizing Uyghurs as a “minority” denies them the right to independence and allows independence efforts to be punished as separatism.

For much of the past decade, international reporting on China’s Uyghur region has followed a grim but familiar pattern: satellite images of internment facilities, testimony from former detainees, and diplomatic disputes over whether Beijing’s policies amount to genocide.

What has received far less attention is a more fundamental question now being raised by scholars: whether the language used to describe the Uyghur people—and the political relationship at the heart of the crisis—has itself constrained how the world understands what is happening.

In a recent study published by Cambridge University Press, Dilnur Reyhan, a senior researcher at the Czech Academy of Sciences, argues that portraying Uyghurs primarily as a “minority” within China obscures a longer history of conquest and domination. Instead, she contends, China’s rule over the region officially known as Xinjiang should be understood as a form of settler colonialism—a framework more commonly associated with European empires than with the modern Chinese state.

The argument arrives amid continued international scrutiny of Beijing’s policies, which include mass surveillance, restrictions on religious practice, and programs critics say amount to forced assimilation. Chinese officials deny wrongdoing, framing their actions as counterterrorism and poverty alleviation, while governments in the United States and Europe have imposed sanctions and accused China of genocide and crimes against humanity.

“If governments and the media explain recent atrocities without addressing the colonial context,” Dr. Reyhan said, “they avoid recognizing the Uyghurs as a colonized people with the right to self-determination.”

“Minority” Is a Political Category

It is always a sociologically dominant group that creates a minority category, particularly in colonial situations.”

An undated screenshot provided by Dilnur Reyhan shows her during a television interview with a French TV station.

At the center of Dr. Reyhan’s argument is the claim that the concept of a “minority” is not merely descriptive, but political.

“We must ask who decides and categorizes a people as a ‘minority,’ and who benefits from this,” she said in an interview. “It is always a sociologically dominant group that creates a minority category, particularly in colonial situations.”

In international law, she noted, the concept of minority rights emerged relatively late and remains undefined in any legally binding way—a gap she attributes to the reluctance of powerful states to allow international law to govern what they consider internal affairs.

This framing, she argues, effectively erases the circumstances under which the Uyghur homeland was annexed into the People’s Republic of China in 1949, following the deployment of the People’s Liberation Army and the collapse of short-lived East Turkestan republics. What followed was colonial governance, including a restructuring of land, population, and political power that she describes as hallmarks of colonial systems.

The consequences, she said, are far-reaching. Categorizing Uyghurs as a “minority” places their political claims outside the realm of legitimate international concern. “Since this people is categorized as a ‘minority,’ it will not have the right to independence, and any action in that direction will be punished legally as a crime of separatism, as an advantage of the minoritization for the colonial state,” she said.

Why Focusing Only on Post-2017 Abuses Falls Short

Much international attention has centered on policies introduced after 2017, when Chinese authorities dramatically expanded internment and surveillance campaigns. While those measures marked a sharp escalation, Dr. Reyhan argues that focusing solely on recent abuses obscures the broader colonial context in which they emerged.

“This focus on recent crimes is deliberate,” she said, referring to governments and global media alike. “It conceals the long historical trajectory of a colonial situation.”

Acknowledging that trajectory, she added, would require confronting questions of self-determination—a step that conflicts directly with Beijing’s official narrative and carries diplomatic consequences.

As a result, recent policies are often treated as exceptional or temporary, not as part of a longer colonial project aimed at securing control over a strategically vital territory.

Why Colonialism Is a Central Concept

“Unlike classical colonialism, which seeks to control an indigenous population, settler colonialism seeks to replace it,” she said. She also rejects the notion of “internal colonialism,” arguing that it ultimately reinforces the legitimacy of the colonial state rather than challenging it.

Applying the concept of colonialism to China remains controversial, even among critics of Beijing’s policies. Many scholars reserve the term for non-Western empires and argue that China’s governance, however coercive, differs from European models of conquest.

Dr. Reyhan rejects that distinction. Based on comparative colonial analysis, she argues that the Uyghur case aligns most closely with settler colonialism—a system in which mass migration and territorial transformation aim to replace the indigenous population over time.

“Unlike classical colonialism, which seeks to control an indigenous population, settler colonialism seeks to replace it,” she said. She also rejects the notion of “internal colonialism,” arguing that it ultimately reinforces the legitimacy of the colonial state rather than challenging it.

Settler colonialism, she added, is a long-term process that inevitably leads to genocide. In her view, failing to recognize it as such limits the ability of international actors to grasp the full scope of what is unfolding.

The Limits of Human Rights Advocacy

“Merely lamenting the Chinese state’s current genocidal crimes without acknowledging its colonial motives only encourages the Chinese colonial state to continue its crimes with impunity until the complete eradication of the Uyghurs as a nation,”

Human rights reporting has played a central role in documenting abuses in the Uyghur region and mobilizing global attention. But critics, including Dr. Reyhan, argue that this framework can also narrow the debate.

“Merely lamenting the Chinese state’s current genocidal crimes without acknowledging its colonial motives only encourages the Chinese colonial state to continue its crimes with impunity until the complete eradication of the Uyghurs as a nation,” she said. “The first step for governments and international actors, including NGOs, the media, and scholars, to put an end to the atrocities that China is inflicting on the Uyghur people is to recognize the colonial situation of the Uyghurs and East Turkestan.”

That narrow framing, she argues, may unintentionally align with Beijing’s portrayal of the crisis as an internal governance issue, even when international actors strongly condemn the policies themselves.

Implications for Journalism and Policy

“Recognizing a people as colonized implies, under international law, recognizing their sovereignty over their territory as an independent nation,”

The study has prompted renewed debate about the role of language in shaping coverage. Terms like “Xinjiang,” which translates as “new frontier,” are routinely used in international reporting despite their colonial origins. Historical context is often condensed or omitted in favor of crisis-driven narratives.

For policymakers, adopting a colonial lens would not dictate a single course of action. But it would challenge the assumption that improved rights protections alone can resolve a conflict rooted in conquest and demographic transformation.

Ultimately, Dr. Reyhan argues, meaningful accountability requires confronting those deeper structures.

“Recognizing a people as colonized implies, under international law, recognizing their sovereignty over their territory as an independent nation,” she said. “In the case of the Uyghurs, as in the case of other nations that have suffered colonization in the past, only the end of colonization and national sovereignty can put a definitive end to mass crimes.”