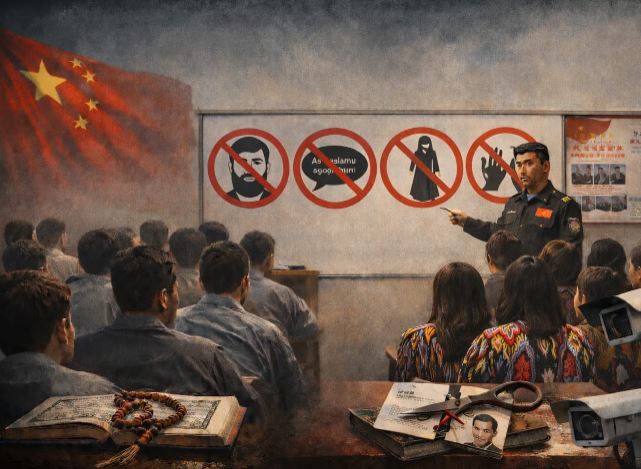

AI generated image of indoctrination session in Kashgar

Leaked audio recording from Chinese government sanctioned indoctrination session reveals Uyghurs still targeted for being "extreme" in 15 different ways

Arslan Hidayat and Nuriman Abdureshid

“Across the region, we all fully took part in this 5-day conference. There are 75 types of extremism, those that took part in the conference you all heard this. Those that did not attend have not been informed. So this is a restaurant, a business place, lunch time is close, we are also embarrassed that we did not finish on time. We are not able to fully tell you everything, so we are going to go through the main 15 points now. Let’s carefully remember these and implement them when you return. It will be good for you comrades. It will be good for us [officials] those you are promoting. So in order to save the time of our comrades I am going to summarize the main points.

The 75 types of religious extremism, I am going to round them down to 15 main points, these are ones that we always come across.

1. Promote and spread religious extremist ideas, so you saw how extremism is expressed, there is no point in me repeating it again, let us be extremely careful in this regard.2. Interfering in others’ religious beliefs, forcing people to take part in religious activities, giving money or property at religious events to religion officials, and forcing others to work for them for free [volunteering is religious duties].

3. Interfere in others’ weddings [Marriage between Uyghurs and Chinese], funerals and inheritance.

4. Interfering in other people’s inter-racial or inter-faith [between Uyghur and Chinese], communication, exchange, in-person meeting, and living together [arrangements].

5. Interfering in cultural and entertainment events. Self-banning and denying material and community services like radio and television.

6. Inappropriately using Islamic [halal-haram] terminology. Using Islamic [halal-haram] terminology outside the scope of food, expanding it into other areas [of life]. Saying something is un-Islamic [haram] to bully and interfere in their modern [Chinese-style] lives.

7. Wearing Niqab [Islamic face covering], wearing extremist symbols and/or forcing others to do so, the wearing of Niqab, meaning since 2017, because of strong promoting and tight restrictions, can no longer be seen. However, among some of them, among 45-55 year olds [you still see] wearing skirts under their pants. This situation is prominent amongst our women [in our region]. We are strengthening our promotion in this regard. All departments, street management, social services, are managing this. What I am saying is, when we say, the modern outfit style is, you young people understand. Something that is light, looks good on your body, something that is breathing especially in the hot weather. Short sleeved, among us there are some that bully people who wear shorter clothes. Interfering in these matters is strictly forbidden.

8. Promoting religious identity by having an abnormal beard, moustache and giving [your child] a religious [Islamic] name. When referring to the beard, some of you chefs, bosses may be aware, especially when working in the restaurant [industry], having a beard and/or moustache is not appropriate. So every three days shave and look clean so that you can be suitable waiters for these good restaurants. We can be good waiters for the restaurant, for the customers and be suitable for the restaurant owners. So for the young men thinking about having a beard, trying to imitate the stars [entertainers]. Stars are stars, there is one [bearded] among a thousand of them. We have some Uyghur stars that have beards, there is no need to imitate, you are not like them, that is their business. That’s why they are living in inner-China, among them [Chinese], we are living in our own region. So when you’re above 60, if we are able to reach that age, then we can have a beard and/or moustache, there is no need to have a beard at this age.

9. Without government approval, marrying or divorcing in a religious [Islamic] fashion.

10. [inaudible] trying to obstruct mandatory public education.

11. Incite and misguide others to go against receiving government benefit policies. Ripping and/or destroying government ID cards, residential household registration booklets, and other government-issued documents.

12. Destroying public and/or private money or property on purpose.13. Publishing, spreading, storing, copying or possessing articles, audio, video, and literature materials that consist of extremist ideology.

14. On purpose, going against or interfering in our state/government [PRC] policies.15. Other signs of extremism in words and actions. It means, like we said before, there are many things included in this. Everyone here has been infected by extremism, including me. All our Uyghur people have been infected by extremism, I am also included. For example, when I got married I had a Nikah [Islamic wedding ritual]. 15 years [ago], we used to make “dua” [raise hands in prayer/supplication] then get up after eating in our neighbour’s house or in larger restaurants. I used to avoid, we all used to avoid [eating Islamically suspicious foods]. Another typical example is, when we look at extremist words and actions like, about not always promoting extremism, before we used to say ‘Assalamualaykum’ when we used to greet each other, we used to say ‘Waalaykumasalam’, when we used to leave the house we used to say ‘Allah be with you,’ we used to do that right? After a hearty meal, we used to say ‘Thanks to Allah,’ [Islamic] all phrases like this. So now, instead of saying ‘Thanks to Allah’ we have now learnt to say ‘Thanks to the Party’. Of course, the party is doing things worth thanking, isn’t that right? Yes, that’s right! Instead of saying ‘Assalamualaykum’ we say ‘Hello, How are you?’ When we are going to leave we now say ‘are you going? Goodbye’. We are using modern words. Like before if we continue to not be thankful, promote the old ways, [inaudible], promoting, spreading extremism. Forcing others… you just heard all this. We will use this criteria and hold ourselves accountable to the law. There is no need to put ourselves in trouble. We need to comply with modern times. Let’s be careful in this regard.”

Kashgar Times has obtained a leaked audio recording from Abduweli Ayup, founder of the Norway-based nonprofit Uyghur Hjelp. For security reasons, we are withholding the date and location of the recording. The audio captures a government-led indoctrination conference for Uyghur workers held in Kashgar, in the south of East Turkistan.

When read closely, the 15 signs reveal something deeper than a security framework. They outline a system where ordinary Uyghur religious, cultural, and social behavior is recast as deviant or dangerous.

Several of the listed signs criminalize basic expressions of faith. Using Islamic terminology beyond food, giving children religious names, wearing certain clothing, growing a beard, or greeting someone with “Assalamu alaykum” are all described as potential indicators of extremism. Even personal habits, such as avoiding food considered religiously questionable or saying “thanks to Allah” after a meal, are presented as behaviors that must be unlearned.

“Learning and Identifying 75 Religious Extreme Activities in Parts of Xinjiang”

In the recording, a government official explains what are described as the “15 Signs of Extremism.” These are presented as a simplified version of the “75 Signs of Religious Extremism” that Chinese authorities have used since at least 2017. Originally released in 2014, “Learning and Identifying 75 Religious Extreme Activities in Parts of Xinjiang” by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Committee of the Chinese Communist Party highlighted various activities and behaviors deemed to be extremism. Dr. Darren Byler has archived, annotated, and translated this document into English from the original Chinese text and became a tool for arbitrary detention, surveillance, and punishment across the region.

The official frames the session as a practical summary for workers and business owners who may not have attended the full conference. The tone is informal and managerial, but the message is clear. These criteria are not abstract guidelines. They are meant to be remembered, applied, and enforced in daily life.

Islam Banned in East Turkistan

Other points target family and community life. Interference in weddings, funerals, inheritance, or education is framed as extremist behavior, particularly when it does not align with state-approved practices. Religious marriage (Nikah) and divorce without government approval are singled out, effectively placing intimate life under political supervision.

The official also emphasizes conformity in appearance and conduct, especially for Uyghurs working in service industries. Men are told to shave every three days to be “suitable” for restaurants and customers. Women’s clothing (Islamic attire) is discussed in detail, with clear pressure to adopt state-defined “modern” styles. These instructions are not presented as advice, but as expectations tied to social acceptance and economic survival.

One of the most revealing moments in the recording comes near the end, when the speaker states that “all our Uyghur people have been infected by extremism,” including himself. He lists past practices that were once normal, such as Islamic wedding rituals, communal prayers, and religious greetings, and labels them as examples of extremism that have now been corrected. Gratitude, he explains, should no longer be directed to God but to the Chinese Communist Party.

“Problematic Songs”: How Uyghur Music Is Criminalized

This is not a marginal comment. It reflects the core logic of the system being described. Extremism is defined so broadly that it includes history, memory, language, and belief. Compliance is framed as modernity. Dissent, or even quiet continuity, is framed as danger.

The final category, “other signs of extremism in words and actions,” leaves the definition intentionally open-ended. It grants authorities the discretion to decide, at any moment, what crosses the line. In such a system, no one can be fully safe, because the rules are not fixed.

What this recording shows is not merely a list of prohibited behaviors. It documents an ongoing effort to reshape Uyghur identity itself. By reducing faith, culture, and social bonds to security risks, the state transforms everyday life into a potential crime scene.

For Uyghurs, reading between the lines is not an intellectual exercise. It is a matter of survival.