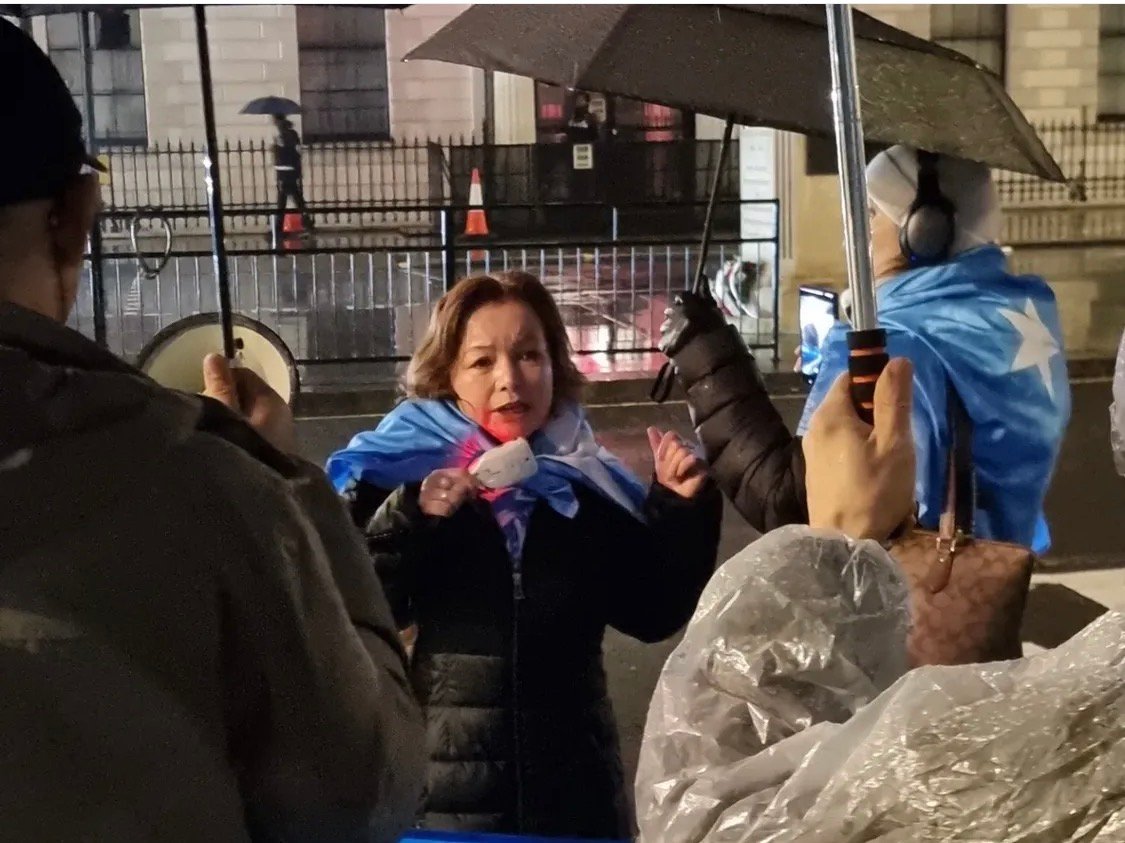

Rahima Mahmut of Stop Uyghur Genocide (second right) with UK Uyghurs outside London’s Chinese Embassy on February 5, 2026, to commemorate the day Chinese forces opened fire killing unarmed protesters. Courtesy of Stop Uyghur Genocide.

It is midwinter, in China’s furthest northwestern frontier, and the ground is frozen solid, with temperatures well below zero. February 4, 1997, sees Chinese authorities arrest hundreds at prayer during Ramadan. On February 5, exasperated by years of increasingly stringent curbs on their religion, their unique culture, and language, thousands of students took to the streets of Ghulja.

Chinese soldiers are mobilized, firing into the crowd, killing scores, and maiming thousands more. Those who avoid the bullets are hosed down with icy water, causing many to suffer severe frostbite of limbs that, for some, are unavoidably amputated later.

A second wave of arrests rounds up thousands, many of whom in the coming days face firing squads in a public arena, watched by crowds who have been frog-marched into the stadium as a dreadful warning against repeating these “treasonous” acts.

Tens of thousands of security forces surround Ghulja to avoid the news reaching the outside world. Those who share information do so amid threats of imprisonment and torture for speaking out.

Despite repeated calls on Beijing by Amnesty International and other human rights groups in the wake of the atrocities, the Chinese government has until now remained silent.

29 years later, however, the event is rehearsed and remembered by Uyghurs as if it were yesterday.

The 1980s had been fraught with unrest in Xinjiang province, now referred to by Uyghur exiles as East Turkestan. Unpopular nuclear testing in the eastern part of the vast Taklamakan Desert had continued apace, and students were already calling for “freedom,” “democracy,” and racial equality with the Han Chinese majority population.

Uyghurs opposed heavily controlled religious activities, and, according to Gardner Bovingdon in his book “The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land,” a set of restrictions was crushing Uyghur morale. Imams had to be state-approved, and Islamic religious observances such as headscarves and long beards were discouraged. Mosque attendance for under-18s was banned.

Social protests in 1995 generated tighter controls over ethnic and religious activities, and 1996’s “strike hard” campaign targeted potential “separatists” with thousands rounded up for “illegal religious activities.”

Amnesty International reported at least a thousand people executed across China between 28 April and 27 June 1996, many after summary trials, and several hundred arrested or sentenced to long jail terms. The arrests in Xinjiang at that time were not due to an increase in crime but to a government push for speed and quantity of arrests.

Experts assessed the increasing frustration and hopelessness among Uyghurs during this period as having kindled the exasperation that led to the 1997 mass demonstration.

A further dimension adding fuel to the fire of government unease was described by Australia-based Arslan Hidayat, of Uyghur campaigning groups “Save Uyghur” and “Justice for All.”

Speaking to “Bitter Winter,” he described the protests in Ghulja as a direct attack on Uyghur religious rights and cultural identity. The traditional Uyghur community gathering known as “Meshrep” had been enjoying a renaissance at the time, he said, and was beginning to successfully tackle some of the prevailing issues of alcohol and heroin abuse among Uyghur youth. The informal and often lighthearted community gathering, integrating music, dance, poetry, conversation, and moral arbitration started to become a threat to the government.

“The Meshrep became so big and influential that you could describe it as a small government, where internal rules and laws were enacted for the general betterment of the Uyghur people,” he said. The fact that it did not involve Chinese government control was a challenge too far.

Captured on film and smuggled out of the country, the UK’s Channel 4 covered subsequent events in a documentary soon after the massacre, recovered by Arslan Hidayat on his Facebook page.

Amnesty International’s 1999 report “Gross violations of Human Rights in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” estimated 200 Uyghurs were executed following the event, but the exact numbers of those executed, arrested, or disappeared could not be confirmed.

Turgunjan Alawudun, President of the World Uyghur Congress, said in a press release to commemorate February 5, that the WUC decried the cultural destruction of the Uyghur people that had continued apace since the massacre. He said it showed Beijing’s ambition to “wipe out the distinct Uyghur cultural character.” He cited the arrest and silencing of Uyghur writers, scholars, poets, artists, religious figures, and anyone in the position of preserving Uyghur culture, particularly since 2016, as clear examples of Beijing’s determination to criminalize his people.

Recent crackdowns on Uyghur-language music by criminalizing its possession and performance in the Uyghur homeland indicate that Beijing is as determined as ever.

“The WUC calls on the international community to reflect on the lessons of Ghulja and take decisive action,” Alawudun said. “As we remember the Ghulja Massacre and acknowledge the suffering of millions of Uyghurs, the WUC emphasizes the importance of collective action against the atrocity crimes.” He urged international support to push for justice and accountability to counter the ongoing atrocities committed with impunity by the Chinese government.

Rahima Mahmut, CEO of UK-based Stop Uyghur Genocide, is a native of Ghulja. The events of February 5 are seared in her memory. She has spoken of the massacre as just one of a “long and ongoing pattern of repression that has since moved into systematic persecution.”

Speaking on the anniversary, she said that February 5, 1997, had been a “defining moment” for her, and one that forced her to leave her homeland in 2000, never able to return. She honored those who stood up to oppression in Ghulja, whose courage “remains a powerful call for justice and freedom.”

“We must not stay silent,” she said. “On this solemn anniversary, we honour those who lost their lives and all who continue to suffer under China’s brutal regime. We carry the spirit of Ghulja, the spirit of defiance, resilience, and hope.”

Omer Kanat, Executive Director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project, urged the international community to respond with greater force. “It has the tools and obligations to respond through sanctions targeting perpetrators of human rights abuses and enforcement of international conventions against genocide and crimes against humanity.”

Ruth Ingram is a researcher who has written extensively for the Central Asia-Caucasus publication, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, the Guardian Weekly newspaper, The Diplomat, and other publications.