Immigration Minister Marc Miller included the proposed resettlement of Uyghur refugees in his plan for Canada's 2024-26 immigration levels. The Hill Times photograph by Andrew Meade

No Uyghur refugees have been resettled in Canada yet, but hope persists that arrivals could begin in November, according to advocate Mehmet Tohti.

| September 18, 2024

Progress has been slow on a new program to resettle Uyghur refugees in Canada as an advocacy group says none have yet to arrive after nine months.

In February 2023, the House of Commons unanimously agreed to call on the government to “urgently leverage” Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) refugee and humanitarian resettlement program to “expedite” 10,000 Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims to come to Canada in 2024 and 2025.

The House of Commons motion sponsored by Liberal MP Sameer Zuberi (Pierrefonds–Dollard, Que.) set in motion the creation of the resettlement program to help vulnerable Uyghurs stuck in third countries in between China and safety.

Zuberi’s motion followed a previous Conservative motion sponsored by MP Michael Chong (Wellington-Halton Hills, Ont.) that passed unanimously in February 2021, which noted it was the House’s opinion that China’s persecution of Uyghurs constituted genocide.

When the federal government unveiled its immigration plan for 2024 to 2026 last November, it included its commitment to Uyghur refugees as part of the number of refugees and protected persons that it was allocated to admit.

Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project (URAP) executive director Mehmet Tohti said the federal government told him that its aim is to bring in 500 Uyghur refugees by the end of the year, with increased numbers coming in 2025 and 2026.

He said he hopes that the target for 2024 will be met, but doubted IRCC would be able to reach it.

“The program is ongoing, [but] most likely we are not going to fulfill the initial 500 arrivals before the end of this year as the IRCC had promised,” he said, remarking that URAP is trying to submit more than 500 individuals to be processed. “There will not be an issue in the number of potential candidates to submit to the IRCC portal.”

“But IRCC itself is stretched out because of the backlog, and they may not be processing the 500 applications before the end of this year,” he said, but noted there has been a promise to bring in 5,000 people in 2025.

While there is concern that the target of resettling 500 this year will be missed, Tohti said that senior government officials have committed to him that the program will be followed through on.

As of right now, Tohti said there has yet to be a Uyghur refugee to reach Canada as part of the new program, noting that he is hopeful that the first arrivals will come to Canada in November.

IRCC spokesperson Michelle Carbert declined to answer how many Uyghur refugees have been resettled in Canada, citing safety concerns as the reason for not providing additional details.

“Our first priority is the safety of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. As such, we are unable to provide further information about our operational efforts as it could put these vulnerable people at further risk,” she said, noting that refugees who have fled China could still face threat while in a third country, including being forced to return.

She said that applications have been received, and processing is ongoing.

The department currently has more than 2.3 million applications on its docket, with more than one million backlogged and taking too long to process.

Zuberi told The Hill Times he is confident that the government will follow through on his motion.

“The wheels have started to turn,” he said, but remarked that he would have liked to have seen the government follow through on the motion as it was written and passed by the House.

The motion called for the 10,000 refugees to be admitted to Canada within two years starting in 2024, but the government gave itself a third year to fulfill the pledge.

“I would have liked to have seen it within the timeline that is within the motion,” he said. “But what we are talking about at the end of the day are deeply vulnerable people—that fact remains.”

“We can talk about timelines here in Canada, [but] that doesn’t change the fact that they are deeply vulnerable, and it has proven that they’ve been [sent] back to the concentration camps in China,” he said.

“We need to remember why we’re doing this. These people are more than numbers,” he said. “We did commit to taking on a certain weight in recognition that Canada has a role to play in this humanitarian crisis and to avert genocide.”

In the last hours of her role in 2022, then-United Nations human rights commissioner Michelle Bachelet submitted a report that found that the extent of Beijing’s arbitrary detention against Uyghurs “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.”

China has consistently denied all charges of international law breaches against Uyghurs.

The Canadian government has been reluctant to label China’s persecution of Uyghurs as a genocide, saying that can only be done by an international tribunal. Global Affairs Canada noted that Canadian Ambassador to China Jennifer May raised concerns over “credible reports of systematic violations of human rights occurring in Xinjiang” during a visit to the region in June.

As the Liberal government has indicated that it will cap certain immigration streams, Tohti said he hopes that any changes to Canada’s immigration regime won’t impact the Uyghur resettlement program.

“The public perception on immigration has changed, so there is a huge concern, and I hope that IRCC should uphold its commitment,” he said.

Provincial premiers have increasingly come out against asylum seekers coming to their provinces.

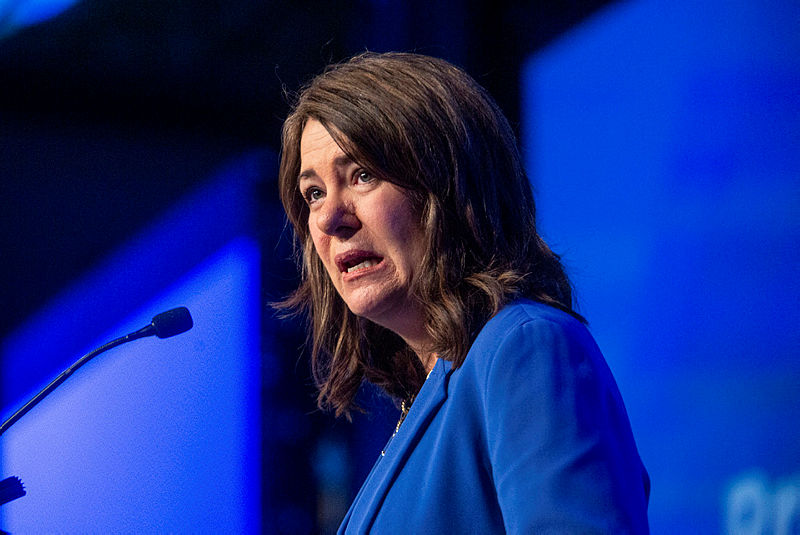

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has opposed the federal government’s plan to adopt a system of “fair distribution” of asylum seekers to have smaller provinces take in more refugees after a call from Quebec Premier François Legault to reduce its share of migrants. Others like New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs have also opposed the Liberal government’s idea.

Despite his concern, Tohti said he has “a certain level of confidence” that the Uyghur resettlement plan will continue as promised since it was voted on with the support of the federal cabinet—including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (Papineau, Que.)—and was supported by all parties.

While Uyghur refugees wait to come to Canada, Tohti said there is a concern for their safety, especially those in Turkey as Ankara grows increasingly close to China. Earlier this month, Turkey announced that it was seeking to join the BRICS group, which includes China, Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa, among others. Turkey signed an extradition treaty with China in 2017, which has been ratified by China, but has yet to be approved by Turkey’s National Assembly.

Tohti highlighted concerns that Turkey could deport Uyghurs to China through a third country.

“There’s a strong desire from the Turkish government to join Chinese-led international organizations, and that is the vulnerability for Turkey [as] China can increase pressure to discuss that extradition treaty in the Turkish parliament and approve it. It can happen,” Tohti said.

Zuberi said speed is crucial in the rollout of the resettlement regime.

“Each day people are not in a country that they can call safe—where they still are at risk being deported to China—is a day more that they are at risk and vulnerable,” he said. “The power of the motion is that it specifically focuses on deeply vulnerable people.”

The Hill Times